Sergej Eisenstein

June 1 to 23, 2006

The influence of Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948) on cinema is unparalleled. His theory of montage was as pioneering as they ways in which he put his ideas into practice. His entire output as a filmmaker is relatively is small (he completed seven feature films), but his influence remains as strong as ever. The "Odessa steps" sequence in Battleship Potemkin (1925) became an emblematic and much-quoted image for Eisenstein's cinematic achievement.

It constitutes only the tip of the iceberg in the oeuvre of a universal scholar, who drew upon influences from all other art forms as well as from religion, anthropology and psychology and endeavoured to unite them in film; in so doing, he created an important basis for the the further development of the medium.

Eisenstein came from a Jewish family of civil engineers and became politicized through the Civil War in 1918. Ordered to the Eastern Front to work as an engineer, Eisenstein encountered Japanese culture for the first time; it was to have a profound influence on him. Above all it was ideograms, the written characters whose meaning changes according to the combination of the individual symbols, which were decisive in helping to form Eisenstein's ideas of dialectic montage.

Editing makes a synthesis possible; from the confrontation between two shots a third and deeper meaning can be drawn. At the climax of Eisenstein's first feature Strike (1924), the suppression of a worker's uprising is contrasted with images of livestock being slaughtered.

After the war, Eisenstein ended up, more or less by chance, with the Proletkult Theatre, where he started out as set designer. He quickly rose to become a director in the early 1920s, but found the theatre too inflexible for his needs. Influenced by Dziga Vertov's experimental newsreels and Lev Kuleshov's montage theories, he turned to film.

The international success of Strike led to a new film commission on the subject of the 1905 Revolution. As a result of Battleship Potemkin, Eisenstein achieved global fame. The follow-up commission for a film on the October Revolution led to his first problems with the state bureaucracy, however. October is the most comprehensive demonstration of Eisenstein's editing concepts, yet shortly before the premiere he was obliged to subject the film to drastic cuts, in order to remove the chief protagonist Trotzky, who had fallen out of favour. Eisenstein's "collision montage" and the intellectual panorama view of the Revolution were attacked as "formalist". In the subsequent hymn to the collectivization of farming (The General Line), he was also obliged to allow certain changes.

His ensuing journey abroad was only to result in unfinished projects, despite a contract in Hollywood; these included the uncompleted episode film Qué viva México! The Mexican material was utilized in several "versions” none of which Eisenstein had a hand in. After his return to Moscow, he was forced to abort his first sound film The Bezhin Meadow (1935-37), due to Party disapproval as well as the onset of heart disease.

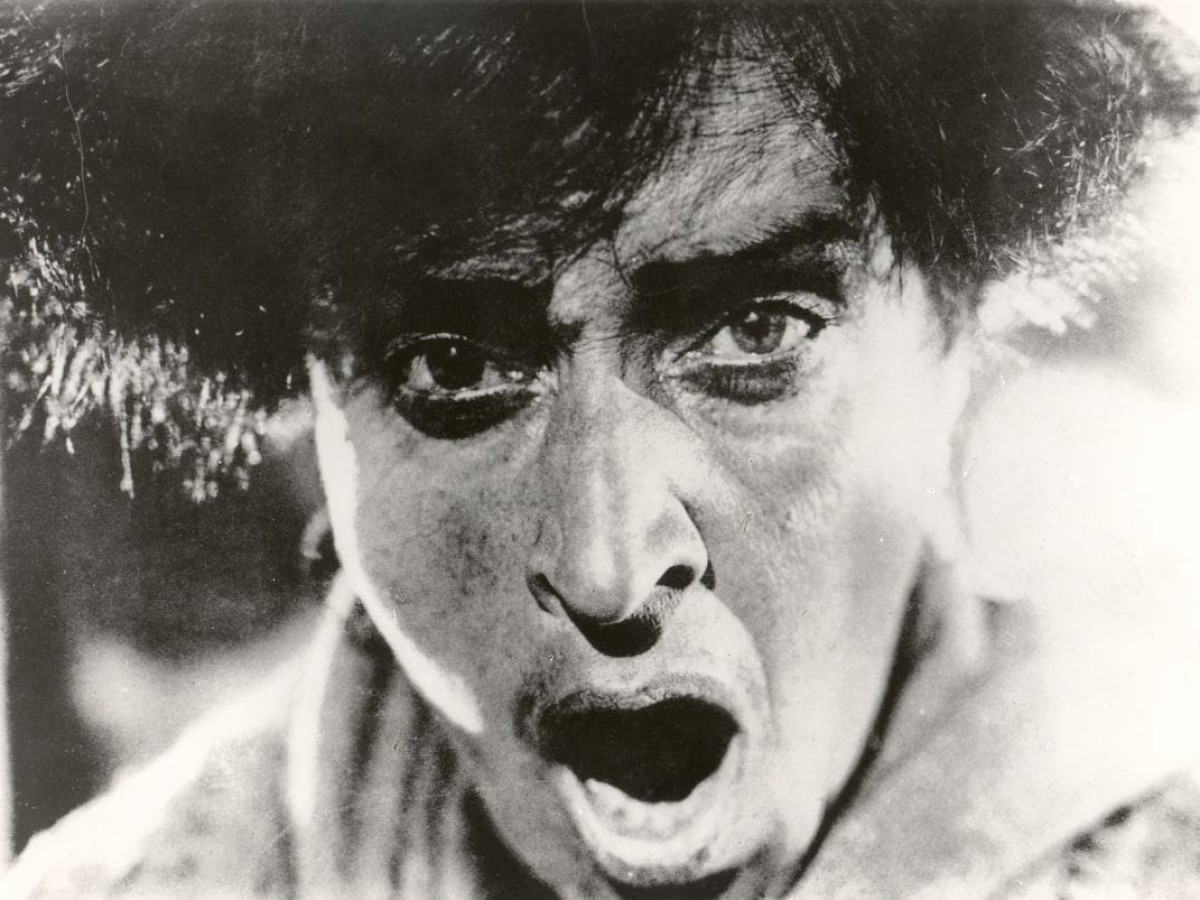

It wasn't until the heroic epic Aleksandr Nevsky (1938), made under strict supervision, that Eisenstein was able to put into practice the ideas from his "sound manifesto" from 1931, thanks also to Sergei Prokofiev's collaboration. Now, as a "reformed" artist, he was permitted to start work on the three-part film Ivan the Terrible. Stalin was delighted with the first part (1944), but rejected the increasingly ambivalent representation of the despotic ruler in the second part. Eisenstein suffered a heart attack after completing the montage, and never fully recovered.

Even without the third part, his final opus Ivan remains a unique achievement. With its extreme stylization influenced by icon painting and Kabuki theatre, and with its novel narrative form, the film is a legacy to what the cinema revolutionary Eisenstein would still have been capable of.

On June 2, Martin Reinhart will present the first elements from a reconstruction of the long-believed-lost early sound version of Potemkin (1930) which he recently discovered in Vienna. This reconstruction, supervised by Enno Patalas and to be finished by the end of the year, is a joint project of the Universität der Künste (Berlin), Technisches Museum und Mediathek (Vienna), Filmmuseum Berlin and the Austrian Film Museum