Martin Scorsese

The Complete Works

August 28 to October 5, 2009

There is no living Hollywood filmmaker whose significance is comparable to that of Martin Scorsese. As a director, he has developed an original, multi-layered and enormously powerful style over more than four decades. His influence on world cinema is immeasurable. Several of his works, such as Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), or Goodfellas (1990) are regularly being ranked among the great classics of American film. As an ardent cinephile, Scorsese has also become the most prominent international figurehead for the preservation and dissemination of film history (as evidenced by his creation of important organisations such as The Film Foundation and the World Cinema Fund, or, to name just one of many other functions, by serving as Honorary President of the Austrian Film Museum). Scorsese's passionate love of cinema is directly transposed into the form of his films; his kinetic and sensuous filmic innovations also stem from assiduous study of his models.

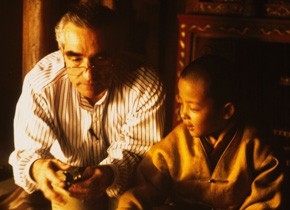

Scorsese, who was born in New York in 1942 and grew up in a Catholic Italian-American environment, once said: "My whole life has been movies and religion." As a young man, he went to seminary; and although he ended up becoming a filmmaker instead, the idea of spirituality pulsates throughout all of his works, culminating most noticeably in his extraordinary films about Jesus (The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988) and the Dalai Lama (Kundun, 1997). However, almost his all his other protagonists are also searching for redemption – they are outsiders, driven and tormented, iconic and broken at the same time; from the neurotic macho in Scorsese’s first feature Who's That Knocking at My Door (1965-68) to the undercover informers in The Departed (2006). They all fulfill their mission, whatever the price: the vigilante Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, the would-be comedian Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1983), the world boxing champ Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, or the self-doubting small-time gangster Charlie in Mean Streets (1973) – a film that delves deeply into the mob world which had fascinated Scorsese while growing up in Little Italy.

In Mean Streets, the rich psychological portrait of a conflicted conscience and the highly detailed and atmospheric representation of the milieu are already inseparable from energetic virtuosity. The contradictions of the characters are as irresistible to Scorsese as the contradictions of their social environment; his films grow out of this friction, they are gripping and physical, yet paradoxically reflective, they portray both “Outer and Inner Space” (to borrow the title of a film by Andy Warhol), they look at cinema and at the world with equal intensity. A frail child, Scorsese absorbed the Hollywood genre cinema as well as Italian Neorealist films which he watched on television; thanks to their dual influence, his unique audiovisual genius is already apparent in his first shorts: the intuitive use of music, the direct, aggressive character of his mise-en-scène and his gift for gritty metaphors. Scorsese's five-minute "Vietnam commentary" The Big Shave (1967) simply shows a young man cutting up his face (to cheerful swing music – violence and comedy are by no means mutually exclusive in Scorsese's works, as his comedies clearly demonstrate). 35 years later, in Gangs of New York, a breathtaking tracking shot stands in for the film's conspicuously absent backdrop -the Civil War which rages in the American interior – when we see soldiers boarding a transport ship while coffins are being unloaded.

Scorsese's cinema is also a personal reflection on American history (and film history). In his filmography, a subtle delineation of the sociocultural prison that is New York's upper crust in the 19th century (in the masterful melodrama The Age of Innocence, 1993) stands alongside the appropriately ambivalent swan song to the American Dream in 1970s and 80s Las Vegas (in his magnum opus Casino, 1995). This same personal approach also defines Scorsese’s important documentary work. He interviews his parents about their lives (in Italianamerican, 1974), invites the viewer to join him on a richly rewarding trip through the cinema of America (1995) and Italy (1999), and follows his love of popular music. He shoots “rockumentaries” on The Band (The Last Waltz, 1978) and the Rolling Stones (2008), traces the roots of the blues to Africa (2003), and assembles a monumental montage-mosaic on Bob Dylan (2005). Music has always provided the heartbeat of Scorsese's films and he regularly comes up with new aspects of the interplay between image and sound. In New York, New York (1977), he pays homage to the classical musical, in Goodfellas, he keeps pace musically with the story's development, from the effervescent pop sound of the Fifties to the psychedelic paranoia of the Seventies, wrapping things up with Sid Vicious' punk version of “My Way”, and he stages Raging Bull as Grand Opera, from the drum rhythm of the boxing punches accompanied by animal hissing up to the screaming duels in aria duets and trios.

Several fruitful and long-term partnerships (most prominently with actor Robert De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker) have accompanied Scorsese's exceptional career, but his own signature always remains as unmistakable as his obsessions. A trace of a self-portrait can be detected in the compulsive reading of Howard Hughes which Scorsese created in The Aviator in 2004. Just like Hughes' airplanes or the automobiles created by Chevrolet, like the musical poetry of Bob Dylan or the art of Andy Warhol, the "Scorsese Machine" has become an indispensable feature of American cultural history.

Our special thanks are due to Martin Scorsese, Emma Tillinger, Kent Jones, Mark McElhatten, Marianne Bower and Thelma Schoonmaker, whose kind help and support made it possible to stage a retrospective of this scope.

The series is also supported by the Public Affairs Section of the U.S. Embassy.