Carl Theodor Dreyer

November 4 to 30, 2011

He worked tirelessly to realize a personal, radical idea of cinema. His achievement won him a singular place in the pantheon. He is the uncompromising filmmaker par excellence: Carl Theodor Dreyer (*1889, Copenhagen; + 1968, Copenhagen).

Even if they had no commercial success upon their initial release and were the subject of controversy and disagreement among critics, films such as La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (1928), Vampyr (1932), Ordet (The Word, 1955) or Gertrud (1964) have long been considered among the outstanding works of film history. Dreyer's artistic ambition and his perseverance in achieving it directly affected his output. His filmography is rather slim – 14 features in 45 years, five of which are sound films: one per decade, if one leaves aside Dreyer’s Swedish "interlude," Två människor (Two People, 1945), which he regarded as a failure.

The result of the director’s commitment to his art is not only an oeuvre of great purity and dazzling intensity, but also a harrowing confrontation with the contradictions of existence. Especially in his later works, this led to highly paradoxical structures, insoluble yet fully coherent. Dreyer’s reach and his many facets may be evoked by a list of filmmakers who share an affinity with him and have drawn strength from his example; such a list would not only include other Scandinavian soul-searchers such as Ingmar Bergman and Lars Von Trier, but also the Mexican Guillermo del Toro, a genius of genre cinema, or Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, whose works display a similar inclination towards “cool” adaptations of literature, finding the bare essence of cinema there.

Behind the dominant clichés associated with Dreyer – the titan of strict, exacting, "transcendental" filmmaking – many antagonistic traits are revealed. While his reputation often rests on the slow, minutely choreographed mise-en-scène of his last films, the director presented himself as a master of montage right from the start. After years spent as a journalist, critic and screenwriter in the flourishing Danish film industry, Dreyer's directorial debut, Praesidenten (The Presidents, 1919), pays tribute to Hollywood: Instead of the prevailing tableau-style, Dreyer relied upon editing techniques derived from Griffith, and the episodic structure of his next film, Blade af Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan's Book, 1921) applies Griffith’s model (Intolerance, 1916) even more directly. Dreyer’s first film also reveals several features that would remain important to him: his use of sparse décor and the striking geometric clarity of his images, his fascination with matters of conscience, and his striving for authenticity.

In the chamber-pieces that followed, Dreyer perfected his sublime use of light, especially in the delicately destructive love triangle, Michael (1924), and in him feminist social satire, Du skal ære din Hustru (Master of the House, 1925) where Dreyer revealed his (quite folksy) sense of humor. With La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc, Dreyer drove his innovations to their peak: the film's nonconformist asthetic, his rapid-fire and almost abstract montage of close-ups (as well as the tortured fervor of Renée Falconetti in the title role) created a singular pull. After the original negative was destroyed in a fire, the perfectionist Dreyer was forced to create an alternate version from the outtakes, which ironically helped secure his later acclaim – via the cine-clubs – as a leading figure of world cinema. (The original version was rediscovered in 1981, in an Oslo mental institution.)

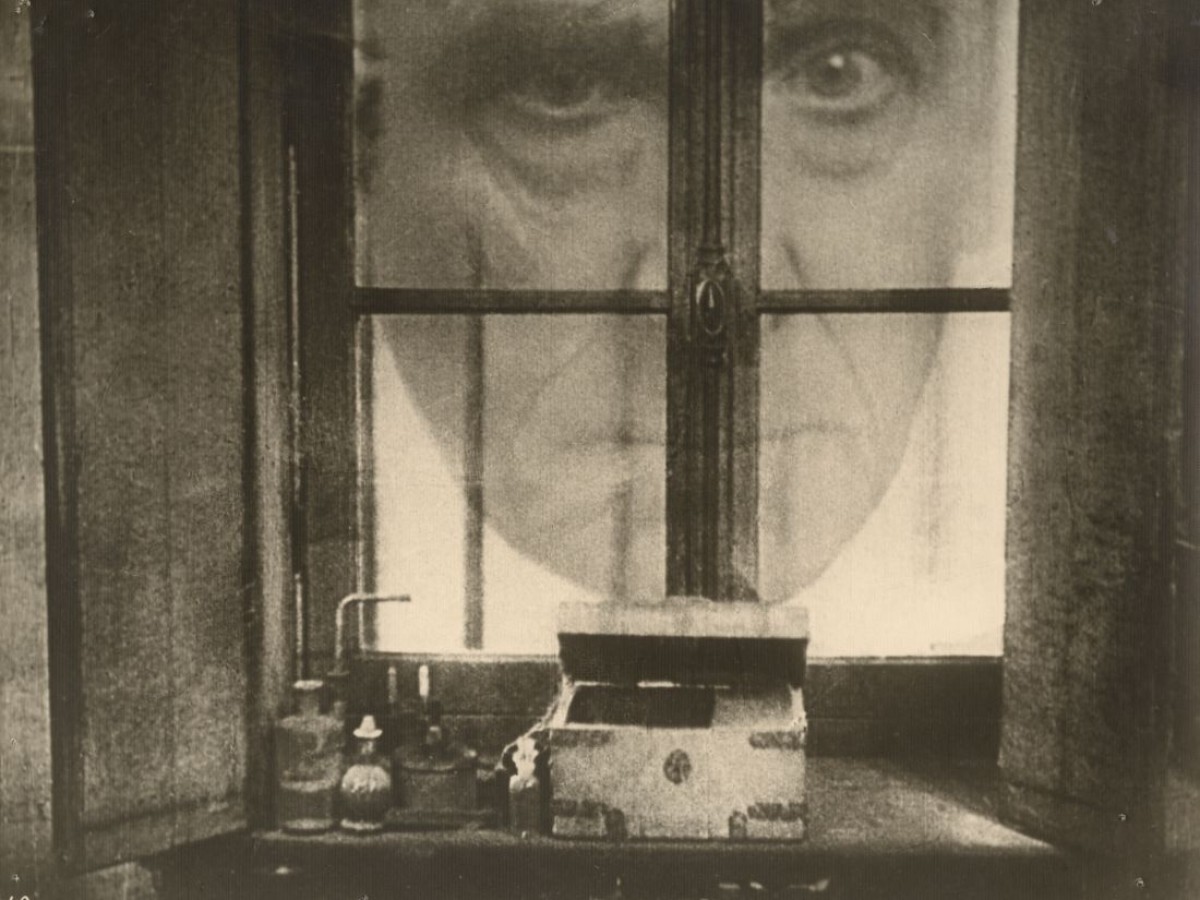

Dreyer felt that "restlessness" was a critical element of "all good films." In his sound films he would convey this quality in groundbreaking and compelling ways: Vampyr, a milestone of horror cinema, breaks with narrative convention to unlock new methods of filmic suggestion (and to convincingly suggest that its director should be seen as a filmmaker of the fantastic). His pronounced spiritualism manifested itself in his portrayal of vampirism as a creeping mental illness; at the same time there is an extraordinary pulse of vibrant sensuality in all of his films: Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943) submerges the viewer in the medieval atmosphere of witch-hunting, while never abandoning a present-day perspective. (One of the camera movements invented by Dreyer can cause hypnotic effects: the camera glides on rails in one direction and pans in another. His ingenuity is also reflected in the remarkable short films that he made on commission during the 1940s and 1950s, for example De nåede færgen [They Caught the Ferry, 1948] with its the terrifically mounting suspense.)

Day of Wrath brings the bold adversarial structure of Dreyer's late films to a head: the "victim" and "perpetrator" are equally and inextricably entangled in a web of sex, superstition and guilt.In Ordet, only a final, "impossible" miracle contradicts the pervasive skepticism (the religious awakening is immediately followed by an eager, slobbery kiss): "A director must believe in the truth of his subjects," said Dreyer: "He must believe in vampires and miracles." Cinema, "the only passion of my life," received some of its greatest miracles from him, and among them is his final work (a 15 year effort to make a film on Jesus was never completed): Gertrud, a study of a woman, her loves and her conscience. Unapproachably rigorous and glowingly tragic, the film is a monument to an almost monstrous martyr – a heroine of intransigence much like Dreyer himself.

The retrospective is organized in close cooperation with the Danish Film Institute, which has preserved and restored many of Dreyer's works in extraordinarily beautiful prints. Thomas Christensen, head of the DFI’s film collection, and Dreyer scholar Casper Tybjerg will give lectures and present rare Dreyer materials from the DFI collection. The program also includes two documentaries about the director, made by Eric Rohmer and Torben Skjødt Jensen.

Related materials

For each series, films are listed in screening order.