The Syrian Modernists

Omar Amiralay, Mohamad Malas, Ossama Mohammed

June 3 to 15, 2015

It is difficult to imagine today that in the 1970s and 1980s, Syria was considered a worldwide pioneer of cinematic modernity, with Omar Amiralay (1944–2011), Mohamad Malas (born 1945) and Ossama Mohammed (born 1954) in the forefront of this development. But was it, in fact, a Syrian movement, or just a handful of filmmakers who were born there? Malas once posed this question when he maintained that a Syrian cinema didn't actually exist because the country had never been able to develop a real culture of film production. Reasons for this abound, as the country never enjoyed the stability needed to build a national cinema – coups and dictatorships, mergers with neighboring states followed by secession, several wars as well as the decades-long autocracy of the Soviet-controlled Baath Party left the Syrian intelligentsia feeling internally restless. Amiralay was the first to move his place of residence to France, where television guaranteed him a certain continuity of work opportunities.

The history of Syria is written in the works of all three men. In his early films, Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1974) and The Chickens (1977), Amiralay took an angry yet satirical stance against the political failures of the Baath leadership; the last film in his oeuvre, A Flood in Baath Country (2003), represents a melancholy yet bitter summation of Syria's era of state socialism. Malas' The Night (1992) ventured another version of the country's oft-fragmented history from the 1930s to the beginning of the 1970s, from the period of the French mandate to the Israeli occupation of the Golan Heights during the Six-Day War and the destruction of al-Quneytrah – a traumatic event that appears in Malas' films like a wound that cannot be closed.

Amiralay and Malas met in the 1970s, when they were co-founders of the Damascus Film Club. They almost never made films together, but were often involved in each other's screenplays. Which is also true of Ossama Mohammed, who arrived somewhat later to this circle. While Amiralay learned his craft at IDHEC in Paris, Malas and Mohammed went to the VGIK (Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography) in Moscow. For Malas, the Soviet modernism of the Khrushchev era was an important influence, whereas Mohammed leaned more heavily on melancholy sketches of Georgian provenance and the Commedia all'italiana. Amiralay ultimately viewed himself as a Brechtian.

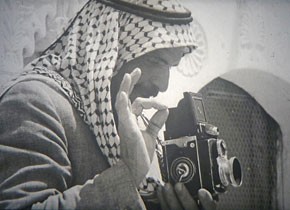

Unlike his more fiction-oriented friends Malas and Mohammed, Amiralay made exclusively documentaries; in addition, he was the one who looked the furthest beyond Syria's borders and pursued a pan-Arab agenda. Together, the three collaborated on two documentaries devoted congenially to their compatriots: a nearly forgotten cinema pioneer (Nazih al-Shahbandar) and a fine arts superstar (Fateh al-Moudarres).

Perhaps they should be viewed thusly: it may well be that no Syrian cinema exists, but the work of these three masters reveals a Syrian cinema which could have existed – which was at one time possible and from which the rest of the world could learn a great deal.

The retrospective is curated by Olaf Möller, who will also present introductions to several programs in the series. The Film Museum is grateful to Mohamad Malas and Ossama Mohammed for their help.