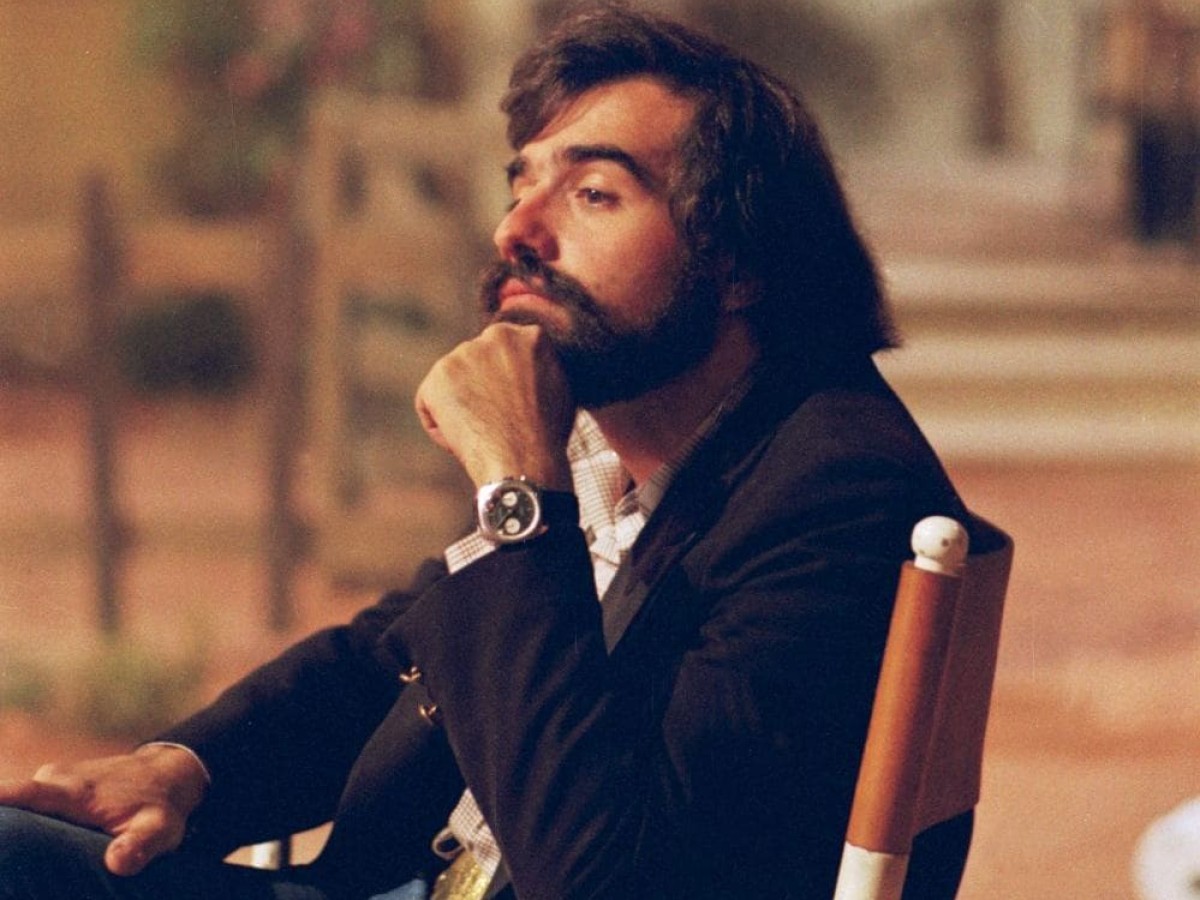

Martin Scorsese

September 1 to October 20, 2022

No other living American filmmaker is as significant as Martin Scorsese. Over more than four decades, the director has developed an original, multilayered, and extremely powerful style with an immeasurable influence on world cinema. Several of his works, including Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), and Goodfellas (1990), are regularly ranked among the great American classics. As an ardent cinephile, Scorsese has also become the most prominent international figurehead for the preservation and dissemination of film history – no less than as Honorary President of the Austrian Film Museum, which will devote a complete retrospective to him in honor of his 80th birthday on November 17, 2022.

Scorsese's passionate love of cinema is directly transposed into the form of his films. His kinetic and sensuous cinematic innovations also stem from the assiduous study of his models: "My whole life has been movies and religion." As a young man, he entered the seminary and, although he ended up becoming a filmmaker instead, the idea of spirituality can be felt in all of his films, culminating most notably in his extraordinary films about Jesus (The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988), the Dalai Lama (Kundun, 1997), and, more recently, Jesuits in 17th century Japan (Silence).

Nearly all of his other protagonists also seek redemption. They are outsiders who are driven and tormented, iconic and broken – from the neurotic macho of his first feature Who's That Knocking at My Door (1965–68) to the undercover informers in The Departed (2006), which earned him an Oscar for best director in 2007, and the life-long criminals in his most recent epic The Irishman. Scorsese's protagonists all fulfill their mission, whatever the price: vigilante Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, would-be comedian Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1983), world boxing champ Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, and self-doubting small-time gangster Charlie in Mean Streets (1973), a film that delves deep into the mob world that fascinated Scorsese while growing up in Little Italy.

In Mean Streets, it is impossible to separate the filmmaker's energetic virtuosity from the rich psychological portrait of a guilty conscience and the highly detailed, atmospheric representation of the milieu. Scorsese cannot resist the characters' personal contradictions any more so than the contradictions of their social environment, and his films grow out of this friction. Gripping and physical, they are also paradoxically reflective. They portray both "Outer and Inner Space" (to borrow the title of a film by Andy Warhol), observing cinema and the world with equal intensity. A frail child, Scorsese absorbed Hollywood genre movies and Italian Neorealism on television. Thanks to their dual influence, his unique audiovisual genius is already visible in his early shorts: an intuitive use of music, the direct, aggressive character of his mise-en-scène, and his gift for gritty metaphors. Scorsese's five-minute "Vietnam commentary" The Big Shave (1967) simply shows a young man cutting up his face (to cheerful swing music – violence and comedy are by no means mutually exclusive in Scorsese's works, as his comedies clearly demonstrate). 35 years later, in Gangs of New York, a breathtaking tracking shot stands in for the film's conspicuously absent backdrop – the Civil War raging in the heart of America – when we see soldiers boarding a transport ship while coffins are unloaded.

Scorsese's cinema is also a personal reflection on American (and film) history. In his filmography, a subtle delineation of the sociocultural prison that is New York's upper crust in the 19th century (in the masterful melodrama The Age of Innocence, 1993) stands alongside the appropriately ambivalent swan song to the American Dream in 1970s and 80s Las Vegas (in his magnum opus Casino, 1995) and its perverse resurrection as a deceitful, high finance farce in the breathtaking late work The Wolf of Wall Street, whose explosive energy proves Scorsese's creativity has not aged one bit.

This same personal approach also defines Scorsese's important documentary work. Alongside the complete retrospective of his feature films, we will also show three select examples of his documentary work that are available on 35mm and that confirm Scorsese's love of popular music: major concert films with The Band (The Last Waltz) and the Rolling Stones (Shine a Light) as well as the search for the roots of the blues (Feel Like Going Home). Music has always provided the heartbeat to Scorsese's films and he regularly finds new ways of combining sound and image. In New York, New York (1977), he pays homage to Hollywood musicals, in Goodfellas, he keeps pace musically with the story's development, from the effervescent pop sound of the fifties to the psychedelic paranoia of the seventies (wrapping things up with Sid Vicious' punk version of "My Way"), and he stages Raging Bull as a Grand Opera, from the drumming rhythm of the boxing punches accompanied by animal hissing to the screaming matches in aria duets and trios.

Scorsese's exceptional career has been accompanied by several fruitful and long-term collaborations (most prominently with actor Robert De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker), but his own signature has always remained as unmistakable as his obsessions. Traces of self-portraiture can be detected in the compulsive reading of Howard Hughes that he created in The Aviator (2004). Just like Hughes' airplanes or cars designed by Chevrolet, like Bob Dylan's musical poetry or Andy Warhol's art, the "Scorsese Machine" has become an indispensable feature in the history of American culture. (Christoph Huber)

A cooperation within the framework of the Austrian American Partnership Fund of the U.S. Embassy in Austria

No other living American filmmaker is as significant as Martin Scorsese. Over more than four decades, the director has developed an original, multilayered, and extremely powerful style with an immeasurable influence on world cinema. Several of his works, including Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), and Goodfellas (1990), are regularly ranked among the great American classics. As an ardent cinephile, Scorsese has also become the most prominent international figurehead for the preservation and dissemination of film history – no less than as Honorary President of the Austrian Film Museum, which will devote a complete retrospective to him in honor of his 80th birthday on November 17, 2022.

Scorsese's passionate love of cinema is directly transposed into the form of his films. His kinetic and sensuous cinematic innovations also stem from the assiduous study of his models: "My whole life has been movies and religion." As a young man, he entered the seminary and, although he ended up becoming a filmmaker instead, the idea of spirituality can be felt in all of his films, culminating most notably in his extraordinary films about Jesus (The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988), the Dalai Lama (Kundun, 1997), and, more recently, Jesuits in 17th century Japan (Silence).

Nearly all of his other protagonists also seek redemption. They are outsiders who are driven and tormented, iconic and broken – from the neurotic macho of his first feature Who's That Knocking at My Door (1965–68) to the undercover informers in The Departed (2006), which earned him an Oscar for best director in 2007, and the life-long criminals in his most recent epic The Irishman. Scorsese's protagonists all fulfill their mission, whatever the price: vigilante Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, would-be comedian Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1983), world boxing champ Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, and self-doubting small-time gangster Charlie in Mean Streets (1973), a film that delves deep into the mob world that fascinated Scorsese while growing up in Little Italy.

In Mean Streets, it is impossible to separate the filmmaker's energetic virtuosity from the rich psychological portrait of a guilty conscience and the highly detailed, atmospheric representation of the milieu. Scorsese cannot resist the characters' personal contradictions any more so than the contradictions of their social environment, and his films grow out of this friction. Gripping and physical, they are also paradoxically reflective. They portray both "Outer and Inner Space" (to borrow the title of a film by Andy Warhol), observing cinema and the world with equal intensity. A frail child, Scorsese absorbed Hollywood genre movies and Italian Neorealism on television. Thanks to their dual influence, his unique audiovisual genius is already visible in his early shorts: an intuitive use of music, the direct, aggressive character of his mise-en-scène, and his gift for gritty metaphors. Scorsese's five-minute "Vietnam commentary" The Big Shave (1967) simply shows a young man cutting up his face (to cheerful swing music – violence and comedy are by no means mutually exclusive in Scorsese's works, as his comedies clearly demonstrate). 35 years later, in Gangs of New York, a breathtaking tracking shot stands in for the film's conspicuously absent backdrop – the Civil War raging in the heart of America – when we see soldiers boarding a transport ship while coffins are unloaded.

Scorsese's cinema is also a personal reflection on American (and film) history. In his filmography, a subtle delineation of the sociocultural prison that is New York's upper crust in the 19th century (in the masterful melodrama The Age of Innocence, 1993) stands alongside the appropriately ambivalent swan song to the American Dream in 1970s and 80s Las Vegas (in his magnum opus Casino, 1995) and its perverse resurrection as a deceitful, high finance farce in the breathtaking late work The Wolf of Wall Street, whose explosive energy proves Scorsese's creativity has not aged one bit.

This same personal approach also defines Scorsese's important documentary work. Alongside the complete retrospective of his feature films, we will also show three select examples of his documentary work that are available on 35mm and that confirm Scorsese's love of popular music: major concert films with The Band (The Last Waltz) and the Rolling Stones (Shine a Light) as well as the search for the roots of the blues (Feel Like Going Home). Music has always provided the heartbeat to Scorsese's films and he regularly finds new ways of combining sound and image. In New York, New York (1977), he pays homage to Hollywood musicals, in Goodfellas, he keeps pace musically with the story's development, from the effervescent pop sound of the fifties to the psychedelic paranoia of the seventies (wrapping things up with Sid Vicious' punk version of "My Way"), and he stages Raging Bull as a Grand Opera, from the drumming rhythm of the boxing punches accompanied by animal hissing to the screaming matches in aria duets and trios.

Scorsese's exceptional career has been accompanied by several fruitful and long-term collaborations (most prominently with actor Robert De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker), but his own signature has always remained as unmistakable as his obsessions. Traces of self-portraiture can be detected in the compulsive reading of Howard Hughes that he created in The Aviator (2004). Just like Hughes' airplanes or cars designed by Chevrolet, like Bob Dylan's musical poetry or Andy Warhol's art, the "Scorsese Machine" has become an indispensable feature in the history of American culture. (Christoph Huber)

A cooperation within the framework of the Austrian American Partnership Fund of the U.S. Embassy in Austria