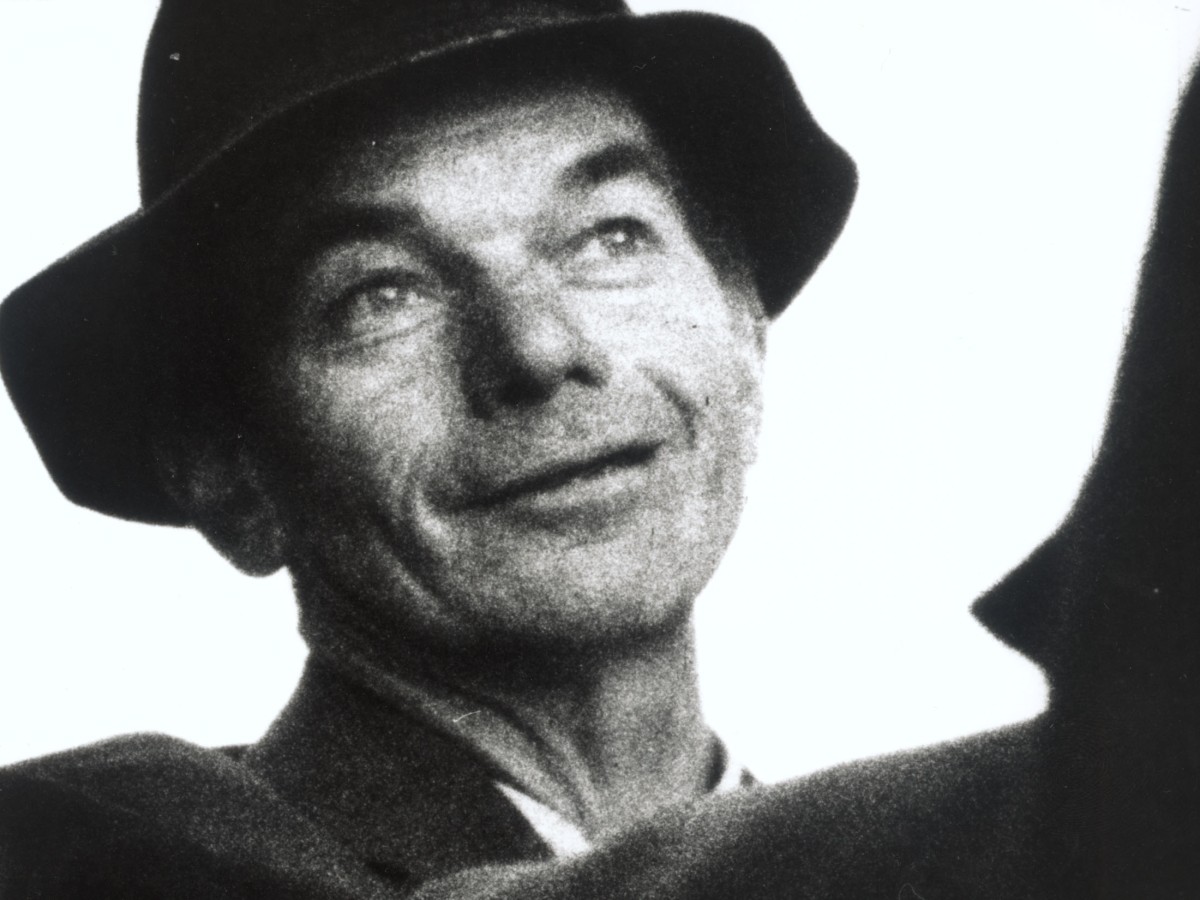

Michael Pilz

November 14 to 30, 2008

Michael Pilz is one of the outstanding figures of modern cinema, yet he is also one of its best-kept secrets, as he has remained virtually unknown and unseen. Pilz, born in a small town in Lower Austria, has realized over 100 works since the 1960s; of these, only two, Himmel und Erde (Heaven and Earth, 1979-82) and Feldberg (1987-90) ever had a regular run in Austrian cinemas. A further handful, including Franz Grimus, Bridge to Monticello and Indian Diary have been registered by critics and cinephiles, but are far from familiar even to the Austrian film public.

In essence, the case of Michael Pilz shows very clearly how much the perception of an artist is dependent on his relationship to the customary logic of film production and distribution. If one leaves the “rules of the game” behind, one risks being entirely marginalized. Outside of film fesitvals or sporadic presentations in the art world context, Pilz's films are hardly ever seen. At the same time, one achieves a very particular kind of freedom going beyond the boundaries – a necessary freedom if one sees art, as Pilz does, primarily as a process and as an act of self-creation, no matter how erratic this “becoming” may be. His oeuvre is appropriately wide-ranging: documentary, feature, experimental, travel and diary films are all represented. Although Pilz’ first filmmaking attempts (with his father's camera) date from the mid-1950s, his first "official" work was achieved in 1964 when he was a student at the Vienna Film Academy. In those years, Pilz was searching for his own path as a filmmaker and everything seemed possible: the relaxed beat of Unter Freunden (Among Friends, 1965) as well as a playfully progressive Euro-genre-cinema which he tried out in Wladimir Nixon (1972). He spent a large part of the 70s working for Austrian Television, without really finding a slot for himself, even though some his principal works were made during this period, such as Franz Grimus and Die Generalin (both 1977). His first completed feature film was a cooperative production: Langsamer Sommer (Slow Summer, 1974-76), an eccentric masterwork under the direction of John Cook.

His breakthrough arrived with a veritable "massif central" of world cinema: Heaven and Earth. This epic work about the Styrian mountain village of St. Anna suddenly turned Pilz into a key figure of Austrian film, which was moving towards a public funding system around this time. Feldberg (1987-90), his second theatrical film, ended up being a thorn in the flesh of precisely the same film subsidy structures. This led to Pilz terminating his contract with the official production world. With Feldberg he had crystalized a cinema of sculpted time; now, with video, he was ready for dissolving time. Pilz’ work in the last two decades has been in a constant state of flux. Some of his unused early material has been taken up and integrated into his "biofilmography".

On occasion, one subject can become the catalyst for several different works, as, for example, with his portraits of the sculptor Karl Prantl and the American director Jack Garfein. In other instances Pilz simply lets his film mature, waiting as long as is needed until the work is ready. One significant example of this is 28. April 1995 Aus Liebe / For Love: Although Brigitte Schwaiger's memoir of her marriage to an officer in Franco's armed forces was shot in 1995, the film was not completed for personal reasons until nine years later, and only made public 13 years later. It will see its première during this Retrospecive, as will Pilz's newest film Jewel of the Valley and Gabriele Hochleitner's portrait of the filmmaker, For Some Friends.

Coinciding with the show, the first book on Michael Pilz, edited by Olaf Möller and Michael Omasta, will be released (Volume 10 of FilmmuseumSynemaPublications).