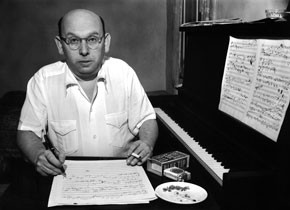

Hanns Eisler

Compositions for Film

April 18 to May 6, 2013

"Hanns Eisler was small in stature, plump, and bald; he dressed without care, smoked too much, drank too much, loved certain desserts and would have laughed uproariously were someone to compare him to a hurricane or a thunderstorm. It sufficed that he went on to become as great as a mountain. Behind his songs, more than just his voice can be heard: his century." (Vladimir Pozner)

It was the century of communism, of mass crowds, of uprisings and subjugation, all of which can be heard in Hanns Eisler's music – the male choirs, the twelve-tone compositions, the music for film and stage, the “new folk songs” ... all of which are hard to separate because Eisler's art was in constant flux, like that of his close accomplice, Bertolt Brecht: a constant renegotiation of existing social relations towards a condition that should ultimately benefit all.

Eisler was an Austrian, even though he was born in Leipzig in 1898 and died in 1962 in East Berlin, and in-between traveled halfway around the world. A few stops along the way: Paris, Moscow, London, Prague, Mexico, the United States, East Germany, and always again, Vienna. Everything in Eisler's life flowed smoothly into one another: his internationalism and musical curiosity, his desire to effect all fronts of the class struggle, the subsequent reprisals and cultural-political power struggles in his "own camp." One day, an Academy Award nomination, the next, a victim of McCarthy; one day, the composer of the East German national anthem, the next, a "homeless cosmopolitan" and "formalist" – two phrases with anti-Semitic connotations that reappeared in 1951/52 during the GDR debates about Eisler's ambitious opera project, Johann Faustus.

Alongside Alban Berg and Anton Webern, Eisler is the most important student of Arnold Schönberg. Yet he cultivated a different vision of modern music and its goals: Eisler's avant-garde found its place not in the bourgeois salons, but in the streets. The advent of the talkie also served him well: film was the new (mass) art of his era and offered him an ideal, and politically interesting, field of experimentation. Some of Eisler's most important film scores stem from this time and his collaborations with innovators like Victor Trivas (Niemandsland and Dans les rues), Brecht and Slatan Dudow (Kuhle Wampe) and Joris Ivens (Komsomol and Nieuwe gronden). Ivens also made the short film Regen (1929), to which Eisler added a terrific piece of dodecaphonic music 12 years later, during his exile in the U.S. (Fourteen Ways to Describe Rain). Along with his score for Alain Resnais' Holocaust-remembrance essay, Night and Fog (1955), Eisler's Rain scoreis perhaps his mightiest piece of film music.

The decade in New York and Hollywood was different for Eisler than for most emigrants, as he was well prepared for a variety of tasks and never lacked work. He taught at the New School for Social Research, was involved in the 1939 World's Fair, and conducted research on his large-scale "Film Music Project" (funded by the Rockefeller Foundation); he composed music for theater and film, and completed masterpieces such as the Deutsche Symphonie and the Hollywooder Liederbuch. With Theodor Adorno in California, Eisler co-wrote the standard text, Composing for the Films, which, because of its criticism of the Hollywood sound as a "lube job," was seen as a contradiction of Eisler's own Hollywood career. But purity was never his goal: the interweaving of "personal" work with commissions was typical of Eisler, as was the constant recycling of musical motifs across all genres.

Eisler's film music often stands in a dialectical relationship to the image. The music is meant to reveal what cannot be seen, showing the audience the "true perspective" of a scene while also commenting on it. The music agitates, deconstructs, and tells as much as the action or the dialogue – and it demands the “reader’s” utmost attention. On occasion, the music also speaks to the collective memory of the audience, as when Eisler quoted leitmotivs from his political “battle songs”. Thus, again and again through the decades, one can hear the themes of his famous Solidarity Song, which today only a few people recognize as Eisler's creation. Perhaps that is as he would have wanted it: the avant-gardist of the masses thus enters the “anonymity” of his listeners.

This program is the most comprehensive presentation of Hanns Eisler's film compositions to date. It is complemented by a lecture and introductions by Johannes C. Gall, who has published numerous works on Eisler and the cinema. Running parallel to the retrospective, Monika Meister will lead a research seminar at TFM at the University of Vienna, focusing on the lifelong collaboration between Eisler and Bertolt Brecht.

Related materials