Henry Fonda for President

August 30 to October 11, 2017

He projected something that reached far beyond the cinematic fictions he served. When he passed away, several obituaries declared him the greatest actor of classical Hollywood cinema. But his talent in this field does not explain the special impact he still has on the American imaginary. Even his reputation as the social "conscience of the nation", most often associated with his role as Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, is only one side of the story. His dark side, epitomized by a propensity for anger and depression, is equally pronounced. Which is why the cliché of the good liberal – represented by the skeptical juror in 12 Angry Men – doesn’t fit him either. The conflict with his part-time rebel children, Jane and Peter, further complicates the situation. Perhaps Henry Fonda’s role in history corresponds to that of a great novelist, as his biographer Devin McKinney suggests. Perhaps his mission was "to step into the American Story, to embody its tragedy and its memory."

Henry Fonda (1905–1982) came from the Midwest: Omaha, Nebraska – flyover country, as it were. He often played men of the land or those who held onto a certain disaffection and exhibited recalcitrance in the face of successful "urbanization," not only in his western roles for John Ford, Anthony Mann or Sergio Leone. As The Magnificent Dope (1942), he made a splendid screwball comedy out of the country bumpkin motif, a mirror image of the stumbling millionaire in love with Barbara Stanwyck in Preston Sturges' The Lady Eve (1941). Fonda possessed great credibility as a man of action as well as a visitor in the realm of comedy and romance. But with him, virility and infatuation were always accompanied by doubt – lending the impression that Fonda's own, biographical “persona” (including formative encounters with mob law, war and suicide) gave off an uncommonly strong echo in his various film characters and stories.

In the 1930s, the fierce American debates about capitalism and democracy infused Fonda and his screen personality with a crucial dynamic culminating in Ford’s magnificent adaptation of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (1940). This persona is the essence of contradiction: a loner and outsider who just as often (sometimes in the very same film) evokes the dream of a better community. He is a man of the Popular Front and he is Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln, using the law as a supple weapon against mob justice and lending democracy the quality of an ungainly dance. At the same time, guilty or innocent, Fonda is a man pursued, telling the story of the American night in You Only Live Once and Let Us Live, two film noir precursors directed by European refugees Fritz Lang and John Brahm. Twenty years later, in one of Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest films, he is still The Wrong Man.

Whether portraying a desperate outcast or an advocate of a just future, he embodies a critical stance towards old America, thereby allowing those citizens who have nothing to do with the ruling powers to strongly identify with him. The gay black author James Baldwin, for example, imagined him as something like a ‘brother from another planet.' Baldwin invites us to re-read Fonda's Tom Joad as he disappears into the image at the end of the film: "White men don't walk like that!"

After three years of military service in the Pacific, a time of self-questioning began for Fonda as well as for the entirety of U.S. cinema. The victory of 1945 did not lead to triumphalism at first, but brought new divisions. What Fonda learnt about death and violence is barely concealed by his emotional reserve in the role of traumatized returnee in Otto Preminger's Daisy Kenyon and another two of Ford's masterpieces, My Darling Clementine and Fort Apache. In the latter, as indicated by Michael Herr, the character of the racist authoritarian Col. Thursday makes the whole of American "mythopathy" visible. Then he decided to take an eight-year break from film. His Broadway comeback (Mister Roberts, a play about the war) became a phenomenal success. In April 1950, on her 42nd birthday, Fonda's second wife Frances committed suicide.

In 1957, The Wrong Man, Anthony Mann's The Tin Star and Sidney Lumet's debut 12 Angry Men (a film Fonda produced himself) announced the third act of his film career, running almost parallel to the Kennedy era. Fonda was over fifty years old at the time. He articulated his hopes for an end to the McCarthy (or "young Mr. Nixon") atmosphere not only by supporting liberal candidates in the political arena, but also through his participation in the short spring of political cinema in Hollywood, made up of films that negotiated the present and future of the Republic and its political caste in the middle of the Cold War. Fonda portrayed the high ambitions and fatal lies of its members with precision in Advise & Consent and The Best Man before taking on the role of incumbent president in Fail-Safe (1964), Lumet's brilliant thriller companion piece to Dr. Strangelove. The setting (the onset of a nuclear war) is eerie precisely because it does not feel like science fiction. This president, carrying within him the promise of young Lincoln as well as the grapes of wrath, becomes the manager of damnation: "What do we say to the dead?"

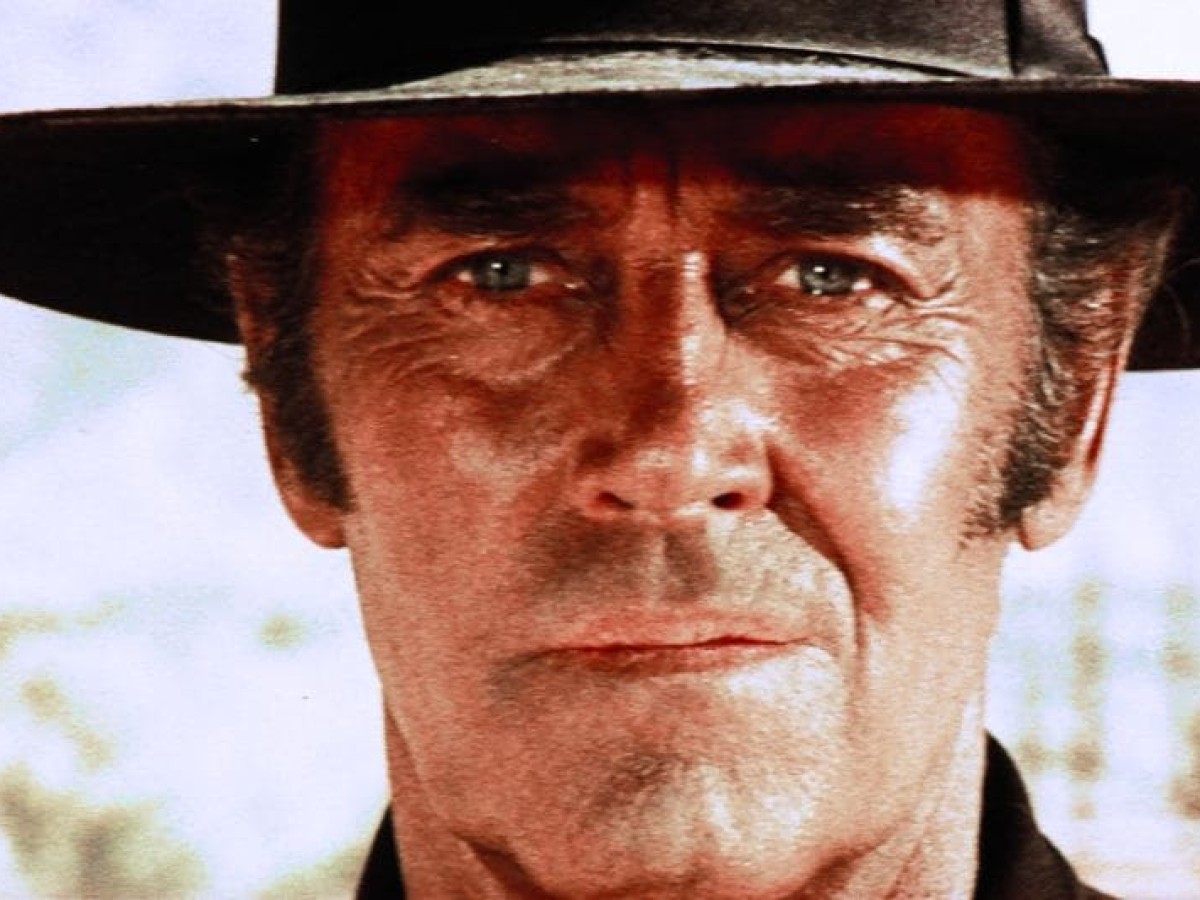

The silence that surrounded him and his often invoked "simplicity" fall short of truly describing Fonda, writes Devin McKinney. Something else is at stake and present in him, something that can be felt, but hardly seen. It is the thing that gives McKinney's book its title: The Man Who Saw a Ghost. It can be found in Fonda's gaze early on: the memory of the dead, doubt, fear, that which is hidden and rarely crosses paths with the controlled visible. When these paths converge, it is we too who see the ghosts. And they do meet at the end of Once Upon a Time in the West, Fonda's very own "1968" where he plumbs the depths of darkness as never before: "This Leone fellow… I've done things for him that I once would have backed away from."

In his last decade, he is America's symbol of the president that never was. "Such fuckin' lies…," he mutters about Richard Nixon in his last interview, and the speeches of his former colleague Ronald Reagan make him "want to throw up." In 1976, he gives a guest performance as himself in the TV sitcom Maude. Politically active housewife Maude has begun an election campaign without consulting him: "Henry Fonda for President!" He flatly rejects; he neither wants to go into politics nor does he have the talent for it: "I'm an actor!" So it was that the actor Henry Fonda did not become president, but a great narrator of the American Century. Just as Barack Obama, a born writer, became president against all odds – thanks to his additional talent as an actor in the tradition of Henry Fonda. The sleep of this tradition produces monsters.