Collection on Screen:

New Hollywood

May 4 to June 28, 2023

The Film Museum has devoted more than one retrospective to the changes in Hollywood in the 1960s and 1970s. Our collection also contains a series of key films from this period that we will exhibit in this module of Collection on Screen. The selection is intentionally limited to feature films and ties into our Collection on Screen series on Italian Neorealism (Fall 2021) and the French Nouvelle vague (early 2022).

The impulses of the New Wave in 1960s France were felt overseas not least as the direct inspiration for the script of Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Ultimately directed by Arthur Penn, the film was initially offered to François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard and counts as the kick-off of New Hollywood: Its audacious tonal shifts from slapstick to violence marked the changing times in the Dream Factory, made possible by the abolition in 1966 of the production code and the years of self-censorship it had imposed.

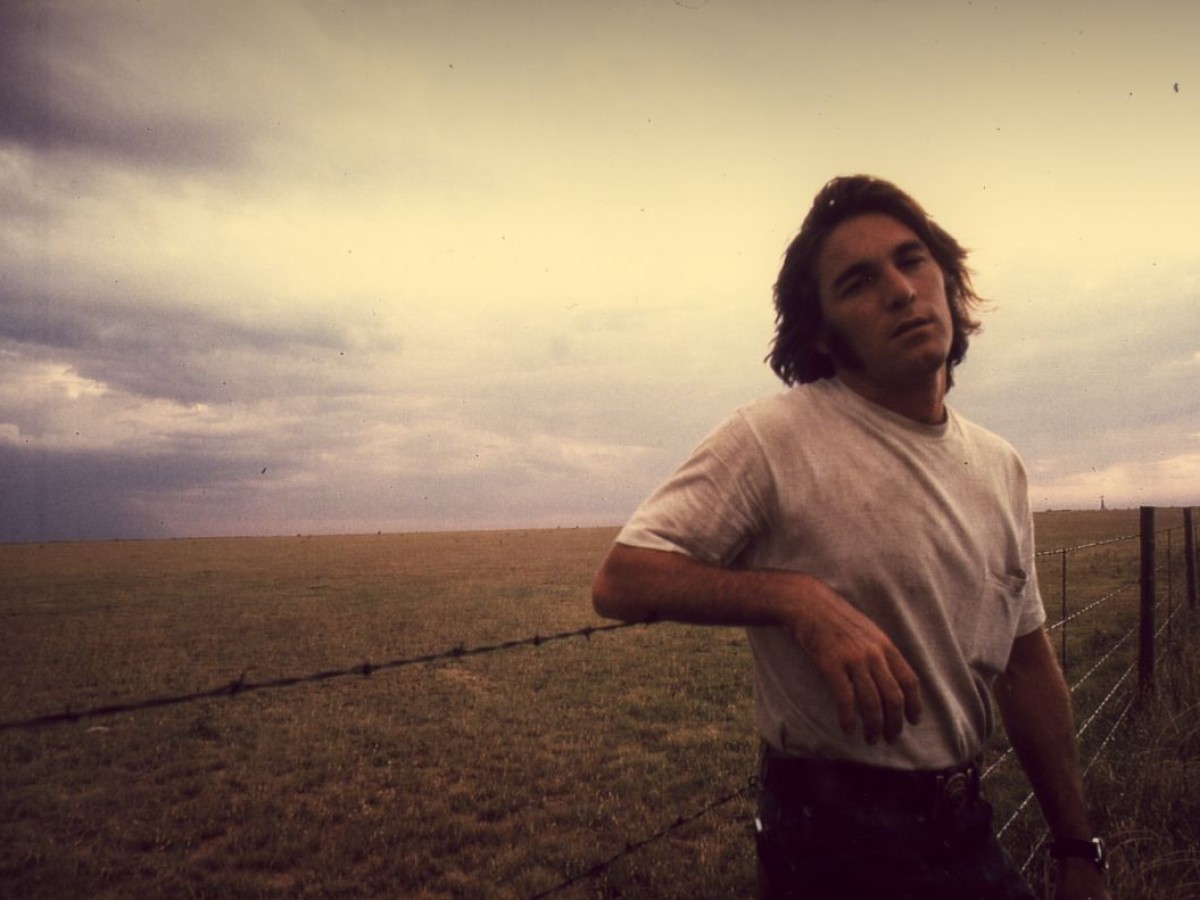

Stand-out Hollywood films like Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks (1961) and John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962) established a cool, modern, personal approach parallel to the Nouvelle Vague while older studio filmmaking disappeared. Bonnie and Clyde counted among the successful projects that triggered a temporary reconceptualization in Hollywood: They wanted to reach younger audiences that had become more interested in modern films from Europe and Asia. Cinephile directors like Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and Walter Hill could try out new ideas, and there was room for political engagement as in Hal Ashby's Shampoo (1975) and, especially, unconventional approaches to genre, from the road movie (Monte Hellmann's Two-Lane Blacktop, 1971) to boxing films (John Huston's Fat City, 1972 – another prime example of the interaction between New Hollywood and the cinema of industry veterans).

The lighter equipment that enabled the defining verité look of the Nouvelle Vague migrated via the parallel documentary movement of Direct Cinema into different achievements like George A. Romero's breakthrough horror film Night of the Living Dead (1968), Barbara Loden's sole feature film Wanda (1970), and John Cassavetes' films and the improvised quality of his work with actors. The openness to the idea of auteur films even led to the importation of European arthouse directors to Hollywood, for instance Michelangelo Antonioni, whose deal with MGM peaked in Professione: reporter/The Passanger (1975), starring Jack Nicholson. And yet the arrival of the blockbuster era and a series of commercial misfires in the 1970s led to the demise of New Hollywood's open-mindedness: In 1983, one of the movement's pioneers, Jim McBride, delivered Breathless, a noteworthy remake of Godard's Nouvelle Vague classic A bout de souffle (1960). It was not, however, a departure like before, but a kind of (rockabilly) swansong. (Christoph Huber / Translation: Ted Fendt)

The Film Museum has devoted more than one retrospective to the changes in Hollywood in the 1960s and 1970s. Our collection also contains a series of key films from this period that we will exhibit in this module of Collection on Screen. The selection is intentionally limited to feature films and ties into our Collection on Screen series on Italian Neorealism (Fall 2021) and the French Nouvelle vague (early 2022).

The impulses of the New Wave in 1960s France were felt overseas not least as the direct inspiration for the script of Bonnie and Clyde (1967). Ultimately directed by Arthur Penn, the film was initially offered to François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard and counts as the kick-off of New Hollywood: Its audacious tonal shifts from slapstick to violence marked the changing times in the Dream Factory, made possible by the abolition in 1966 of the production code and the years of self-censorship it had imposed.

Stand-out Hollywood films like Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks (1961) and John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962) established a cool, modern, personal approach parallel to the Nouvelle Vague while older studio filmmaking disappeared. Bonnie and Clyde counted among the successful projects that triggered a temporary reconceptualization in Hollywood: They wanted to reach younger audiences that had become more interested in modern films from Europe and Asia. Cinephile directors like Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and Walter Hill could try out new ideas, and there was room for political engagement as in Hal Ashby's Shampoo (1975) and, especially, unconventional approaches to genre, from the road movie (Monte Hellmann's Two-Lane Blacktop, 1971) to boxing films (John Huston's Fat City, 1972 – another prime example of the interaction between New Hollywood and the cinema of industry veterans).

The lighter equipment that enabled the defining verité look of the Nouvelle Vague migrated via the parallel documentary movement of Direct Cinema into different achievements like George A. Romero's breakthrough horror film Night of the Living Dead (1968), Barbara Loden's sole feature film Wanda (1970), and John Cassavetes' films and the improvised quality of his work with actors. The openness to the idea of auteur films even led to the importation of European arthouse directors to Hollywood, for instance Michelangelo Antonioni, whose deal with MGM peaked in Professione: reporter/The Passanger (1975), starring Jack Nicholson. And yet the arrival of the blockbuster era and a series of commercial misfires in the 1970s led to the demise of New Hollywood's open-mindedness: In 1983, one of the movement's pioneers, Jim McBride, delivered Breathless, a noteworthy remake of Godard's Nouvelle Vague classic A bout de souffle (1960). It was not, however, a departure like before, but a kind of (rockabilly) swansong. (Christoph Huber / Translation: Ted Fendt)

Related materials

Link Film Collection

Film Series Collection on Screen

Blog Following Film Introduction to Duel by Drehli Robnik (in German)

Film Series Collection on Screen

Blog Following Film Introduction to Duel by Drehli Robnik (in German)