A Second Life

Theme and Variation in Film

October 14 to November 30, 2016

The dominant image of cinema today gives the impression of an impoverished monoculture. Its formula is well known: remakes of successful content and figure "universes" succeeding one another in an increasingly shorter time span, acting as mere serial installments on a repeat loop. At the same time, film industry vocabulary has spread to every sphere of cinematic discourse. The ubiquitous remake is thus accompanied by terms that weigh down any "newness" with an oppressive lack of imagination: reboot, sequel and prequel, spin-off, relaunch and, most recently, re-quel – sequel and remake in one.

The retrospective A Second Life confronts this tendency toward conformity with an intensive look back at the richness of forms that cinema, since its inception, has discovered when reworking older material. Instead of serving only as a vehicle of commercial calculation, in which the endless regeneration of uniformity drives out all else, revision was one option among many, highlighting the decisive, cinematographic differences through apparent similarities in subject or idea.

This phenomenon is particularly striking in adaptations of the same literary source, which shine in a different light when placed in different hands, eras, countries and keys. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, one of the most adapted and modified plays, turns into a silent comedy in Ernst Lubitsch's Romeo und Julia im Schnee (Romeo and Juliet in the Snow), which transplants the story to the alpine countryside, the very setting where Romeo und Julia auf dem Dorfe (via Gottfried Keller's novella as an intermediate step) succeeds as a poetic tragedy of nature and masterpiece of Swiss cinema. Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest, a pioneering work of 1920s hard-boiled crime fiction, went on to become the secret template for key films of completely different genres on various continents: Asian action cinema in Kurosawa's Yōjimbō, spaghetti western in Leone's For a Few Dollars More, and, returning to its U.S. gangland terrain, in the Coen brothers' Miller's Crossing – a harbinger of "indie" neo-noir.

Adaptations of Emily Brontë's famous novel Wuthering Heights are equally diverse: from William Wyler's "classical" Hollywood adaptation to Luis Buñuel's soaringly surrealist Abismos de pasión and Jacques Rivette's spectral modernization Hurlevent. Another trio of works draws a specific socially critical line through film history: the class snobbery of Douglas Sirk's intoxicating American Technicolor melodrama All That Heaven Allows (1955) is transformed by Sirk's admirer Rainer Werner Fassbinder into a story of passion in a migrant-proletarian setting in Angst essen Seele auf (Ali: Fear Eats the Soul), while Todd Haynes takes it back to the American fifties in Far From Heaven, emphasizing taboo issues of the time, such as racism and homosexuality.

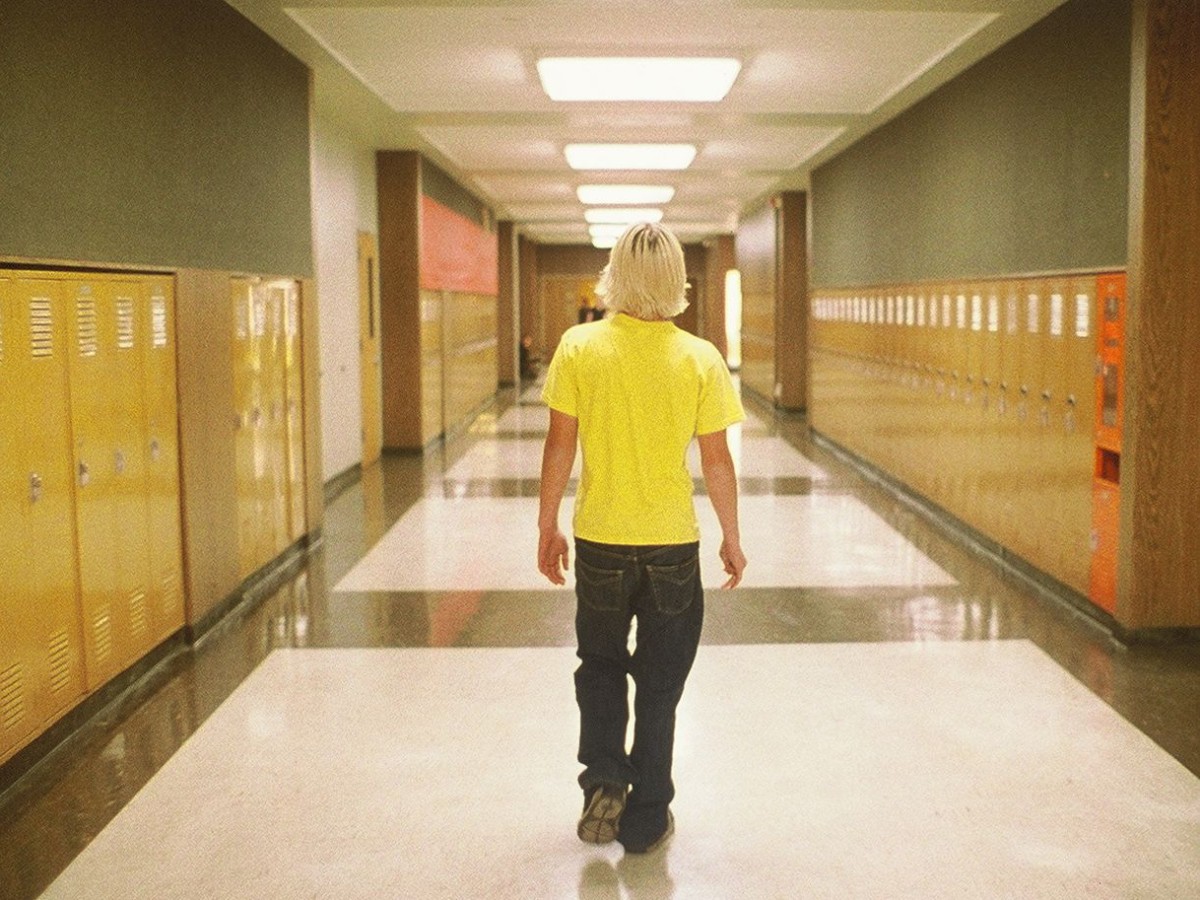

Master directors such as Ozu or Hitchcock remade their early films later in life from a more mature perspective. Others entered into a productive dialogue with one another by attempting variations that are still unique, as in the case of Joseph Losey’s underrated postwar "version" of Fritz Lang's Berlin masterpiece M (1931) – both produced by Seymour Nebenzahl, a German exile in Hollywood. Alan Clarke's uncompromising Elephant about a hit man during the Troubles was the inspiration for Gus Van Sant's 2003 Cannes winner based on a U.S. school shooting – while Josef von Sternberg's abridged Dostoyevsky adaptation Crime and Punishment (1935) starring Peter Lorre meets an epically free transposition from the Philippines: Lav Diaz's Norte, the End of History (2013).

There is a wide range of approaches to the challenge of reworking an existing subject: an inspired parody paying tribute to the "serious" original in a truly captivating manner (as in the classic comedy Airplane! which draws on the forgotten airplane melodrama Zero Hour!) or a film character updated a quarter of a century later (pool player Eddie Felson/Paul Newman in Robert Rossen's The Hustler and Martin Scorsese's The Color of Money). In 1953, independently of each other, two great Italian filmmakers – Michelangelo Antonioni and Vittorio Cottafavi – adapted the "Lady of the Camellias" for the harsh postwar era. And in 1954/55, two brilliant B-films, which at first glance seem like horses of a different color, negotiated the exact same archetypes and constellations: the small-town crime drama Violent Saturday and the Civil War western The Raid, both written by Sydney Boehm and co-starring Lee Marvin.

The question of originality in a remake or revision can only be answered by looking at the actual artistic means applied by a filmmaker, even in a case that might seem like pure theft. Quentin Tarantino's revenge fantasy Kill Bill: Vol.1, profoundly influenced by the Japanese cult film Lady Snowblood, is one such example. Based on a real event, the bizarre idea at the heart of the award-winning Mexican film El castillo de la pureza returns in another festival laureate, the Greek film Dogtooth, where it is handled in an entirely original way. However, instead of dwelling on plagiarism (and thereby feeding another conformist discourse of our era), on the example of these and other films in the retrospective, we can observe that cinema never simply files away its themes and motifs. As long as it is practiced by artists instead of bookkeepers, cinema will never stop providing its stories and inventions with another, an always different life.

"A Second Life" is a joint project of the Austrian Film Museum and the Viennale.

The dominant image of cinema today gives the impression of an impoverished monoculture. Its formula is well known: remakes of successful content and figure "universes" succeeding one another in an increasingly shorter time span, acting as mere serial installments on a repeat loop. At the same time, film industry vocabulary has spread to every sphere of cinematic discourse. The ubiquitous remake is thus accompanied by terms that weigh down any "newness" with an oppressive lack of imagination: reboot, sequel and prequel, spin-off, relaunch and, most recently, re-quel – sequel and remake in one.

The retrospective A Second Life confronts this tendency toward conformity with an intensive look back at the richness of forms that cinema, since its inception, has discovered when reworking older material. Instead of serving only as a vehicle of commercial calculation, in which the endless regeneration of uniformity drives out all else, revision was one option among many, highlighting the decisive, cinematographic differences through apparent similarities in subject or idea.

This phenomenon is particularly striking in adaptations of the same literary source, which shine in a different light when placed in different hands, eras, countries and keys. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, one of the most adapted and modified plays, turns into a silent comedy in Ernst Lubitsch's Romeo und Julia im Schnee (Romeo and Juliet in the Snow), which transplants the story to the alpine countryside, the very setting where Romeo und Julia auf dem Dorfe (via Gottfried Keller's novella as an intermediate step) succeeds as a poetic tragedy of nature and masterpiece of Swiss cinema. Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest, a pioneering work of 1920s hard-boiled crime fiction, went on to become the secret template for key films of completely different genres on various continents: Asian action cinema in Kurosawa's Yōjimbō, spaghetti western in Leone's For a Few Dollars More, and, returning to its U.S. gangland terrain, in the Coen brothers' Miller's Crossing – a harbinger of "indie" neo-noir.

Adaptations of Emily Brontë's famous novel Wuthering Heights are equally diverse: from William Wyler's "classical" Hollywood adaptation to Luis Buñuel's soaringly surrealist Abismos de pasión and Jacques Rivette's spectral modernization Hurlevent. Another trio of works draws a specific socially critical line through film history: the class snobbery of Douglas Sirk's intoxicating American Technicolor melodrama All That Heaven Allows (1955) is transformed by Sirk's admirer Rainer Werner Fassbinder into a story of passion in a migrant-proletarian setting in Angst essen Seele auf (Ali: Fear Eats the Soul), while Todd Haynes takes it back to the American fifties in Far From Heaven, emphasizing taboo issues of the time, such as racism and homosexuality.

Master directors such as Ozu or Hitchcock remade their early films later in life from a more mature perspective. Others entered into a productive dialogue with one another by attempting variations that are still unique, as in the case of Joseph Losey’s underrated postwar "version" of Fritz Lang's Berlin masterpiece M (1931) – both produced by Seymour Nebenzahl, a German exile in Hollywood. Alan Clarke's uncompromising Elephant about a hit man during the Troubles was the inspiration for Gus Van Sant's 2003 Cannes winner based on a U.S. school shooting – while Josef von Sternberg's abridged Dostoyevsky adaptation Crime and Punishment (1935) starring Peter Lorre meets an epically free transposition from the Philippines: Lav Diaz's Norte, the End of History (2013).

There is a wide range of approaches to the challenge of reworking an existing subject: an inspired parody paying tribute to the "serious" original in a truly captivating manner (as in the classic comedy Airplane! which draws on the forgotten airplane melodrama Zero Hour!) or a film character updated a quarter of a century later (pool player Eddie Felson/Paul Newman in Robert Rossen's The Hustler and Martin Scorsese's The Color of Money). In 1953, independently of each other, two great Italian filmmakers – Michelangelo Antonioni and Vittorio Cottafavi – adapted the "Lady of the Camellias" for the harsh postwar era. And in 1954/55, two brilliant B-films, which at first glance seem like horses of a different color, negotiated the exact same archetypes and constellations: the small-town crime drama Violent Saturday and the Civil War western The Raid, both written by Sydney Boehm and co-starring Lee Marvin.

The question of originality in a remake or revision can only be answered by looking at the actual artistic means applied by a filmmaker, even in a case that might seem like pure theft. Quentin Tarantino's revenge fantasy Kill Bill: Vol.1, profoundly influenced by the Japanese cult film Lady Snowblood, is one such example. Based on a real event, the bizarre idea at the heart of the award-winning Mexican film El castillo de la pureza returns in another festival laureate, the Greek film Dogtooth, where it is handled in an entirely original way. However, instead of dwelling on plagiarism (and thereby feeding another conformist discourse of our era), on the example of these and other films in the retrospective, we can observe that cinema never simply files away its themes and motifs. As long as it is practiced by artists instead of bookkeepers, cinema will never stop providing its stories and inventions with another, an always different life.

"A Second Life" is a joint project of the Austrian Film Museum and the Viennale.

Related materials

Link Viennale