Liliana Cavani / Marco Bellocchio

January 11 to February 29, 2024

This year, our traditional kick off with Italian cinema is a dual retrospective devoted to Liliana Cavani (born in 1933) and Marco Bellocchio (born in 1939). The series connects directly to last year's honoring the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pier Paolo Pasolini (and some of his contemporaries): Bellocchio and Cavani represent the next generation of filmmakers from Emilia-Romagna who gained worldwide attention in the 1960s and 1970s by taking (like Pasolini) their own path between auteurist and mainstream cinema. "Our interest was in a new cinema that dealt with the problems of our times. We were interested in the psychology of politics," Cavani would later say, summarizing a few of their commonalities. With its Holocaust-set, sadomasochistic love story between Dirk Bogarde and Charlotte Rampling, her renowned, controversial Vienna-shot film The Night Porter / Il portiere di notte (1974) can be regarded as the culmination of this idea, but in reality the ties between their films are far deeper and substantial: Theirs is a multilayered cinema of uncertainty – psychological and political, but also material and spiritual, consciously mythological and often satirical. Bellocchio established himself as one of the leading voices in this new direction in Italian filmmaking with his furious debut feature I pugni in tasca (Fists in the Pocket, 1965) which tells the grimly humorous story of a decadent bourgeois family's extinction by a son – filmed in his own family's country house and with their money.

Cavani and Bellocchio are not only related by their enigmatic ambivalence but also in their varied approaches. "My work always oscillates between cinema, theater, and documentary film to keep me uninhibited as a director," Bellocchio once went on record as saying. Despite all their differences, the same applies to Cavani. Both went to Rome to study directing and made their first short films in 1961 at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. Not only was Cavani the only woman in her class, winning a competition immediately gave her the opportunity to work for the public broadcaster RAI. She established her stylistic basis with ambitious documentaries about history, researching subjects that had always interested her: A study of female resistance fighters in World War II led to The Night Porter and in 1966 she was able to direct her first made-for-TV movie about Francis of Assisi (featuring Bellocchio in a small role as an intellectual follower protesting the teachings of the later saint) – she would return several times to this character, most prominently in her theatrical feature Francesco (1989) starring Mickey Rourke.

Cavani's first theatrical feature Galileo (1968) also started as a TV production. However, after the censors banned it from being broadcast, she found a distributor. Impressed by the protests of '68, Cavani further sharpened her stories of conflicts with power in I cannibali (The Cannibals, 1969), staging Sophocles' Antigone in contemporary Milan. After dealing with myth, psychiatry (L'ospite, 1972), and spirituality (the Pasolini-praised film Milarepa, 1973), The Night Porter introduced a new international direction to Cavani's career through world stars and co-productions, while she nevertheless remained faithful to her vision: "My films are not historical, they are films about ideas." Al di là del bene e del male (Beyond Good and Evil, 1977), an erotic drama about a love triangle around Friedrich Nietzsche starring Erland Josephson and Dominique Sanda, led to more controversy, as did her Malaparte adaptation Il pelle (The Skin, 1981), a ruthless portrait of chaos and exploitation in Naples at the end of World War II starring Marcello Mastroianni, Burt Lancaster, and Claudia Cardinale. Meanwhile, Cavani had begun staging operas and did so increasingly in the 1990s before working again for television after her riveting Highsmith thriller Ripley's Game (2002, starring John Malkovich). With L'ordine del tempo (The Order of Time, 2023), she has recently made a surprising return to cinema: an atypical apocalyptic film, relaxed and full of old-age wisdom.

Bellocchio remains active as well, and more successful than ever: Concurrent with the retrospective, his latest film Rapito (Kidnapped, 2023) will receive a theatrical release, as has been the case for a series of his masterpieces over the past decade, including the incomparable Mafia epic Il traditore (The Traitor, 2019). After nearly 60 years, it seems the time is finally ripe to discover Bellocchio as the most important living Italian director, someone who despite his early successes remained a kind of unknown giant on the margins of international film culture: His works were presented and received prizes at festivals from Cannes to Venice, but only sporadically visible in regular releases abroad, although within Italy no one doubted his world-class stature. One reason for this may well be that Bellocchio has always been interested in Italian situations and subjects, even while telling universal stories, while directors like Cavani (or Bernardo Bertolucci, after Pasolini the fourth and youngest of the unofficial Emilia-Romagna group) were more internationally oriented. In exchange, Bellocchio (with now over 50 feature and short films to his name) could build a consistent filmography, although he made no secret of working for a long time in a psychological state of crisis – at least until he found a new partner in Francesca Calvelli, who had left her mark on his work since 1994 as his editor. Bellocchio's body of work can be roughly divided into two phases. The first could be labelled his long march through institutions – a series of group portraits in which he systematically dissects various branches of society: The family in I pugni in tasca, party (and politics) in La cina è vicina (China is Near, 1967), the media (and politics) in the political thriller Sbatti il mostro in prima pagina (Slap the Monster on Page One, 1972), the military in Marcia trionfale (Victory March, 1975). In the latter two films especially, one of Bellocchio's talents becomes particularly noticeable, which he would master in his late works: His skill at combining the enthralling pull of genre films with the complex ambivalence of his auteurist vision – e.g. the weight of melodrama, which collides with the story of Mussolini's first wife in Vincere (2009), or with a true story of euthanasia that caused a political stir in Bella addormentata (Sleeping Beauty, 2013), whereas Il traditore, for instance, takes the Mafia film and turns it inside out.

While Bellocchio initially moved parallel to Cavani in social, mythical, and spiritual zones – his militant collective documentary Matti da slegare (Fit to be Untied, 1975) can also be understood as an answer to her L'ospite, which he criticized – his work changed under the influence of controversial anti-Freudian psychoanalyst Massimo Fagioli when he began participating in Fagioli's "collective analysis" group sessions. Only then did his films start to feature ambiguous dream images, now one of his hallmarks. In the award-winning drama Salto nel vuoto (A Leap in the Dark, 1980), starring Michel Piccoli and Anouk Aimée, a number of Fagioli's concepts are illustrated literally. The psychoanalyst directly collaborated on three more films, starting with Il diavolo in corpo (Devil in the Flesh, 1985), which also caused controversy due to an un-simulated sex scene, leading Bellocchio (like Cavani previously) briefly into speculative turmoil between tabloid malice and condescending arts and culture pieces. The fact that Bellocchio was confronting his own doubts in the collaboration with his psychoanalyst was viewed just as suspiciously as his Marxist roots, even though he had long felt disillusioned by politics.

Critics also had trouble categorizing Bellocchio's films because their (presumed) changes of direction and departures were always mystifying, even as his signature remained unmistakable. Like Cavani, who first studied literature, in Bellocchio's adaptations – from Kleist to Pirandello – he has always managed to make the material his own; and the shifts between fiction and documentary modes are felt even more strongly in his films than in Cavani's (alone because of the larger filmography). Above all, however, the two are united by their openness to contradiction: Their examination of power and relations that can possibly be changed. Nothing expresses this better than the dream sequence at the end of his daring chamber piece Buongiorno, notte (Good Morning, Night, 2004) about the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered Bellocchio's international renaissance. There, he provides flashes of an alternative future: A different Italy that was (or would have been) possible. Regarding his reconstruction of the past, in Buongiorno, notte or the futurism-obsessed study of fascism Vincere, Bellocchio once said something beautiful that would fit Cavani just as well and that explains the complexity of their work: "It is all faithful to the truth and completely invented at the same time." (Christoph Huber / Translation: Ted Fendt)

The retrospective presents the complete theatrical films of Lilian Cavani, including the Austrian premiere of her new film L'ordine del tempo (2023), and the majority of Marco Bellocchio's films, as far as rights and print availability allow.

This year, our traditional kick off with Italian cinema is a dual retrospective devoted to Liliana Cavani (born in 1933) and Marco Bellocchio (born in 1939). The series connects directly to last year's honoring the 100th anniversary of the birth of Pier Paolo Pasolini (and some of his contemporaries): Bellocchio and Cavani represent the next generation of filmmakers from Emilia-Romagna who gained worldwide attention in the 1960s and 1970s by taking (like Pasolini) their own path between auteurist and mainstream cinema. "Our interest was in a new cinema that dealt with the problems of our times. We were interested in the psychology of politics," Cavani would later say, summarizing a few of their commonalities. With its Holocaust-set, sadomasochistic love story between Dirk Bogarde and Charlotte Rampling, her renowned, controversial Vienna-shot film The Night Porter / Il portiere di notte (1974) can be regarded as the culmination of this idea, but in reality the ties between their films are far deeper and substantial: Theirs is a multilayered cinema of uncertainty – psychological and political, but also material and spiritual, consciously mythological and often satirical. Bellocchio established himself as one of the leading voices in this new direction in Italian filmmaking with his furious debut feature I pugni in tasca (Fists in the Pocket, 1965) which tells the grimly humorous story of a decadent bourgeois family's extinction by a son – filmed in his own family's country house and with their money.

Cavani and Bellocchio are not only related by their enigmatic ambivalence but also in their varied approaches. "My work always oscillates between cinema, theater, and documentary film to keep me uninhibited as a director," Bellocchio once went on record as saying. Despite all their differences, the same applies to Cavani. Both went to Rome to study directing and made their first short films in 1961 at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. Not only was Cavani the only woman in her class, winning a competition immediately gave her the opportunity to work for the public broadcaster RAI. She established her stylistic basis with ambitious documentaries about history, researching subjects that had always interested her: A study of female resistance fighters in World War II led to The Night Porter and in 1966 she was able to direct her first made-for-TV movie about Francis of Assisi (featuring Bellocchio in a small role as an intellectual follower protesting the teachings of the later saint) – she would return several times to this character, most prominently in her theatrical feature Francesco (1989) starring Mickey Rourke.

Cavani's first theatrical feature Galileo (1968) also started as a TV production. However, after the censors banned it from being broadcast, she found a distributor. Impressed by the protests of '68, Cavani further sharpened her stories of conflicts with power in I cannibali (The Cannibals, 1969), staging Sophocles' Antigone in contemporary Milan. After dealing with myth, psychiatry (L'ospite, 1972), and spirituality (the Pasolini-praised film Milarepa, 1973), The Night Porter introduced a new international direction to Cavani's career through world stars and co-productions, while she nevertheless remained faithful to her vision: "My films are not historical, they are films about ideas." Al di là del bene e del male (Beyond Good and Evil, 1977), an erotic drama about a love triangle around Friedrich Nietzsche starring Erland Josephson and Dominique Sanda, led to more controversy, as did her Malaparte adaptation Il pelle (The Skin, 1981), a ruthless portrait of chaos and exploitation in Naples at the end of World War II starring Marcello Mastroianni, Burt Lancaster, and Claudia Cardinale. Meanwhile, Cavani had begun staging operas and did so increasingly in the 1990s before working again for television after her riveting Highsmith thriller Ripley's Game (2002, starring John Malkovich). With L'ordine del tempo (The Order of Time, 2023), she has recently made a surprising return to cinema: an atypical apocalyptic film, relaxed and full of old-age wisdom.

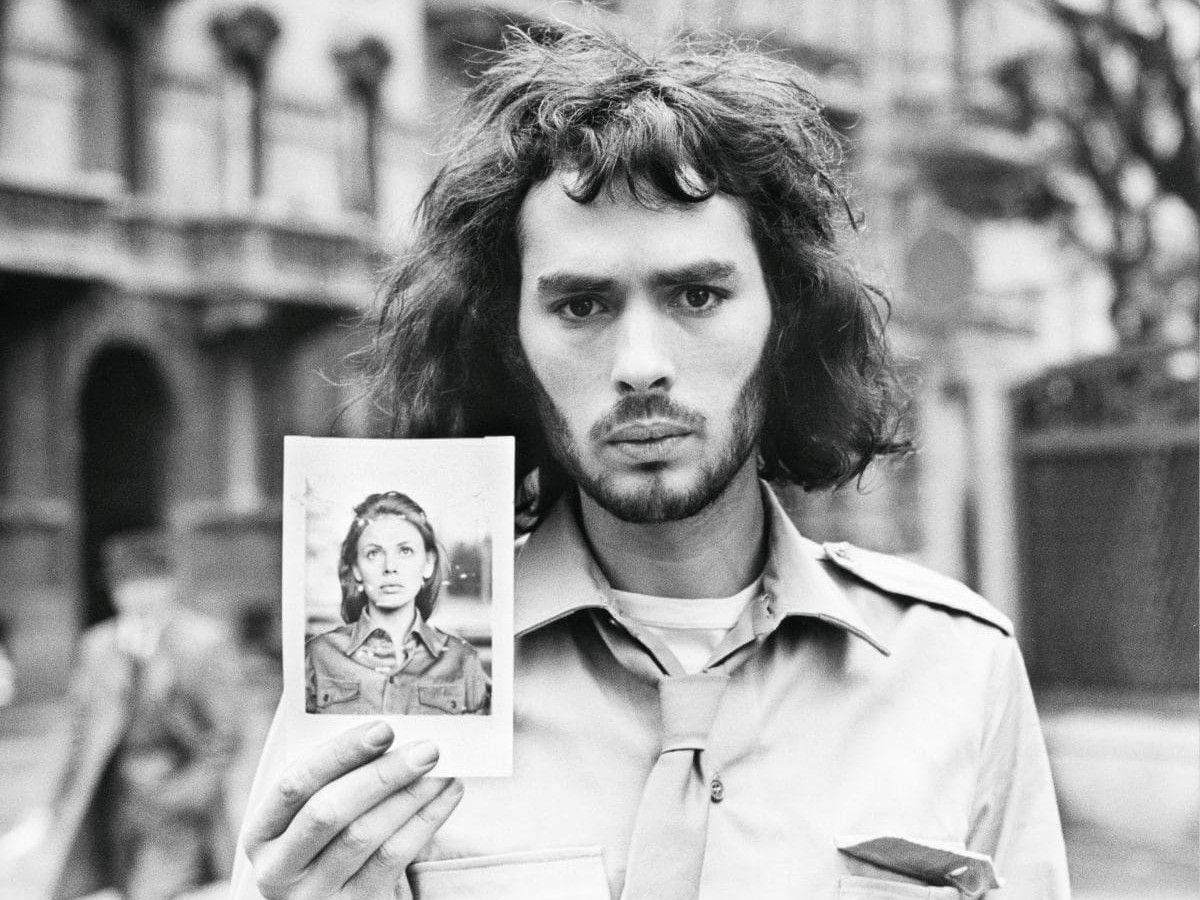

Bellocchio remains active as well, and more successful than ever: Concurrent with the retrospective, his latest film Rapito (Kidnapped, 2023) will receive a theatrical release, as has been the case for a series of his masterpieces over the past decade, including the incomparable Mafia epic Il traditore (The Traitor, 2019). After nearly 60 years, it seems the time is finally ripe to discover Bellocchio as the most important living Italian director, someone who despite his early successes remained a kind of unknown giant on the margins of international film culture: His works were presented and received prizes at festivals from Cannes to Venice, but only sporadically visible in regular releases abroad, although within Italy no one doubted his world-class stature. One reason for this may well be that Bellocchio has always been interested in Italian situations and subjects, even while telling universal stories, while directors like Cavani (or Bernardo Bertolucci, after Pasolini the fourth and youngest of the unofficial Emilia-Romagna group) were more internationally oriented. In exchange, Bellocchio (with now over 50 feature and short films to his name) could build a consistent filmography, although he made no secret of working for a long time in a psychological state of crisis – at least until he found a new partner in Francesca Calvelli, who had left her mark on his work since 1994 as his editor. Bellocchio's body of work can be roughly divided into two phases. The first could be labelled his long march through institutions – a series of group portraits in which he systematically dissects various branches of society: The family in I pugni in tasca, party (and politics) in La cina è vicina (China is Near, 1967), the media (and politics) in the political thriller Sbatti il mostro in prima pagina (Slap the Monster on Page One, 1972), the military in Marcia trionfale (Victory March, 1975). In the latter two films especially, one of Bellocchio's talents becomes particularly noticeable, which he would master in his late works: His skill at combining the enthralling pull of genre films with the complex ambivalence of his auteurist vision – e.g. the weight of melodrama, which collides with the story of Mussolini's first wife in Vincere (2009), or with a true story of euthanasia that caused a political stir in Bella addormentata (Sleeping Beauty, 2013), whereas Il traditore, for instance, takes the Mafia film and turns it inside out.

While Bellocchio initially moved parallel to Cavani in social, mythical, and spiritual zones – his militant collective documentary Matti da slegare (Fit to be Untied, 1975) can also be understood as an answer to her L'ospite, which he criticized – his work changed under the influence of controversial anti-Freudian psychoanalyst Massimo Fagioli when he began participating in Fagioli's "collective analysis" group sessions. Only then did his films start to feature ambiguous dream images, now one of his hallmarks. In the award-winning drama Salto nel vuoto (A Leap in the Dark, 1980), starring Michel Piccoli and Anouk Aimée, a number of Fagioli's concepts are illustrated literally. The psychoanalyst directly collaborated on three more films, starting with Il diavolo in corpo (Devil in the Flesh, 1985), which also caused controversy due to an un-simulated sex scene, leading Bellocchio (like Cavani previously) briefly into speculative turmoil between tabloid malice and condescending arts and culture pieces. The fact that Bellocchio was confronting his own doubts in the collaboration with his psychoanalyst was viewed just as suspiciously as his Marxist roots, even though he had long felt disillusioned by politics.

Critics also had trouble categorizing Bellocchio's films because their (presumed) changes of direction and departures were always mystifying, even as his signature remained unmistakable. Like Cavani, who first studied literature, in Bellocchio's adaptations – from Kleist to Pirandello – he has always managed to make the material his own; and the shifts between fiction and documentary modes are felt even more strongly in his films than in Cavani's (alone because of the larger filmography). Above all, however, the two are united by their openness to contradiction: Their examination of power and relations that can possibly be changed. Nothing expresses this better than the dream sequence at the end of his daring chamber piece Buongiorno, notte (Good Morning, Night, 2004) about the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered Bellocchio's international renaissance. There, he provides flashes of an alternative future: A different Italy that was (or would have been) possible. Regarding his reconstruction of the past, in Buongiorno, notte or the futurism-obsessed study of fascism Vincere, Bellocchio once said something beautiful that would fit Cavani just as well and that explains the complexity of their work: "It is all faithful to the truth and completely invented at the same time." (Christoph Huber / Translation: Ted Fendt)

The retrospective presents the complete theatrical films of Lilian Cavani, including the Austrian premiere of her new film L'ordine del tempo (2023), and the majority of Marco Bellocchio's films, as far as rights and print availability allow.

In collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute Vienna, the Cineteca Nazionale, and Cinecittà

Link

Video introductions by Marco Bellocchio on our YouTube channel