Luigi Zampa & Luciano Salce

Comedy and Character

January 9 to February 26, 2025

Combining razor-sharp satire and popular entertainment, the commedia all'italiana was world renowned between the 1950s and the 1980s. In 2010, we dedicated a major retrospective to this national genre and have subsequently explored its many varieties in other contexts, but there still remains much to discover in the wide field of Italian comedy. To start off the year, we turn to two underappreciated directors who perfectly concentrate the commedia's essence of satire and social critique: In the pointed, contemporary filmic documents of Romans Luigi Zampa (1905–1991) and Luciano Salce (1922–1989), we find a comprehensive and unsparing portrait of social and moral progress.

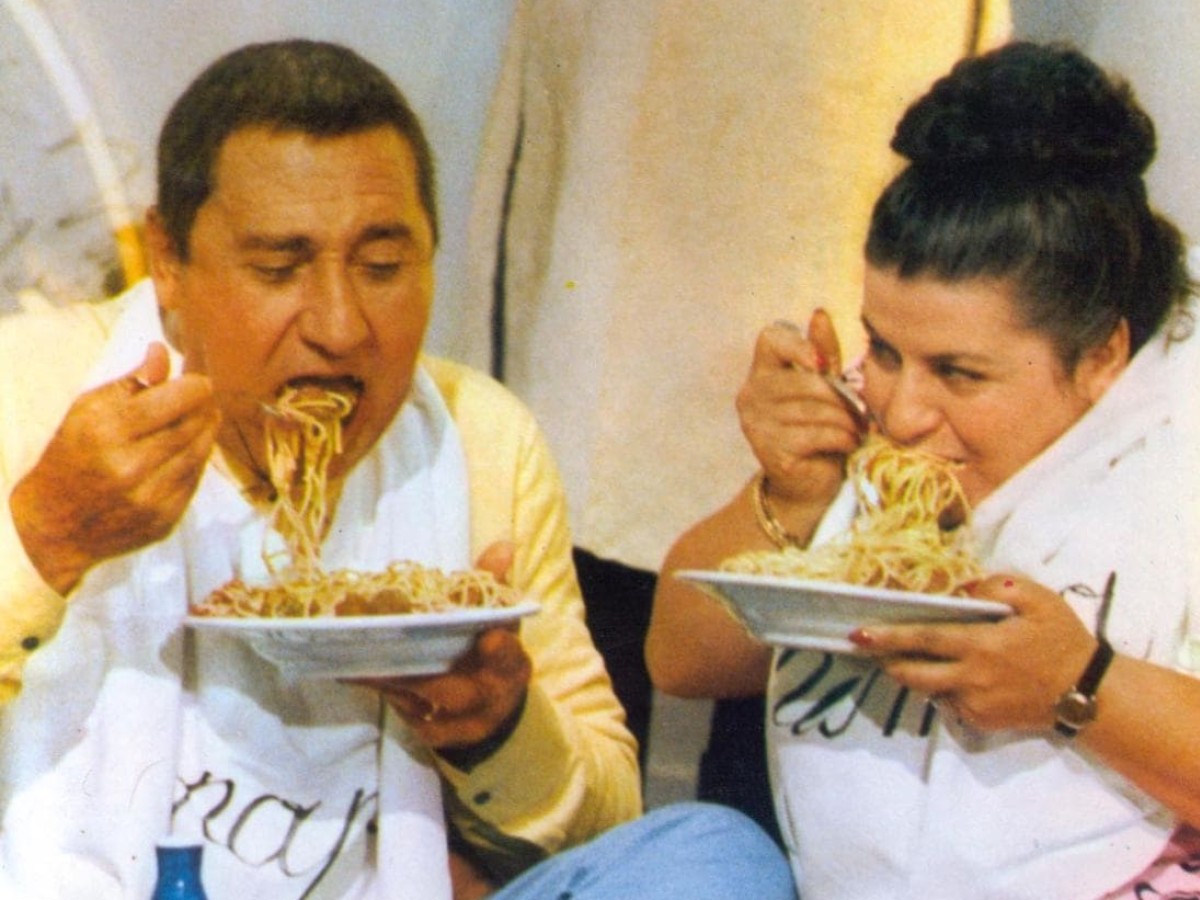

There is a direct lineage between Zampa's classic moral comedy Anni difficili (Difficult Years, 1948) and its grappling with the fascist era, and the side-splitting anthology about the frustrated existence of middle class salaried workers in Salce's brilliant one-two punch Fantozzi (1975) and Il secondo tragico Fantozzi (1976) with Paolo Villaggio in the title role. Power and obedience, corruption and the urge for social recognition, and corruptibility and blind infatuation are recurring themes. L'arte di arrangiarsi (The Art of Getting Along, 1955) is the not-so-ambiguous title of one of Zampa's major works, in which a small municipal clerk (master mime Alberto Sordi) smoothly and spinelessly slips from one political regime to the next between 1913 and 1953: socialist, fascist, communist, Christian democrat – the perfect opportunist.

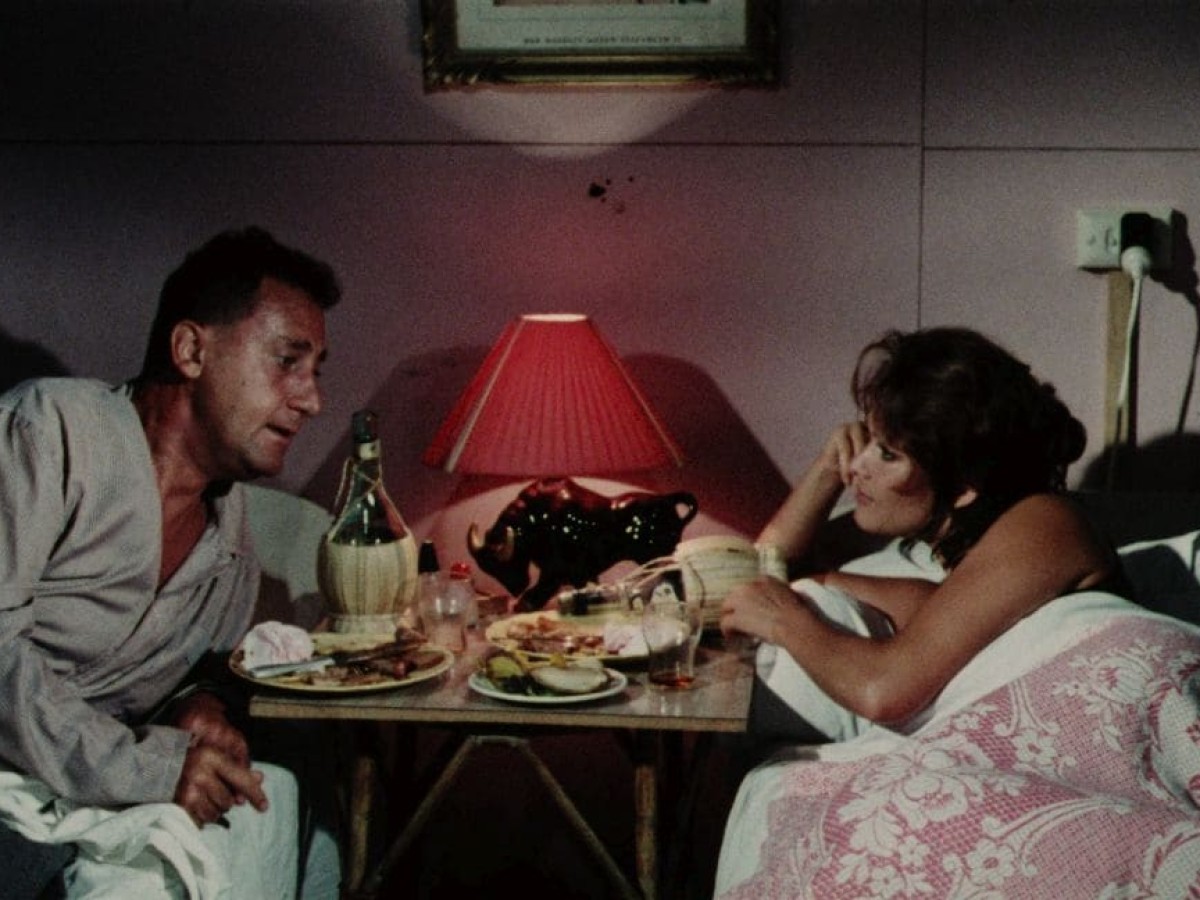

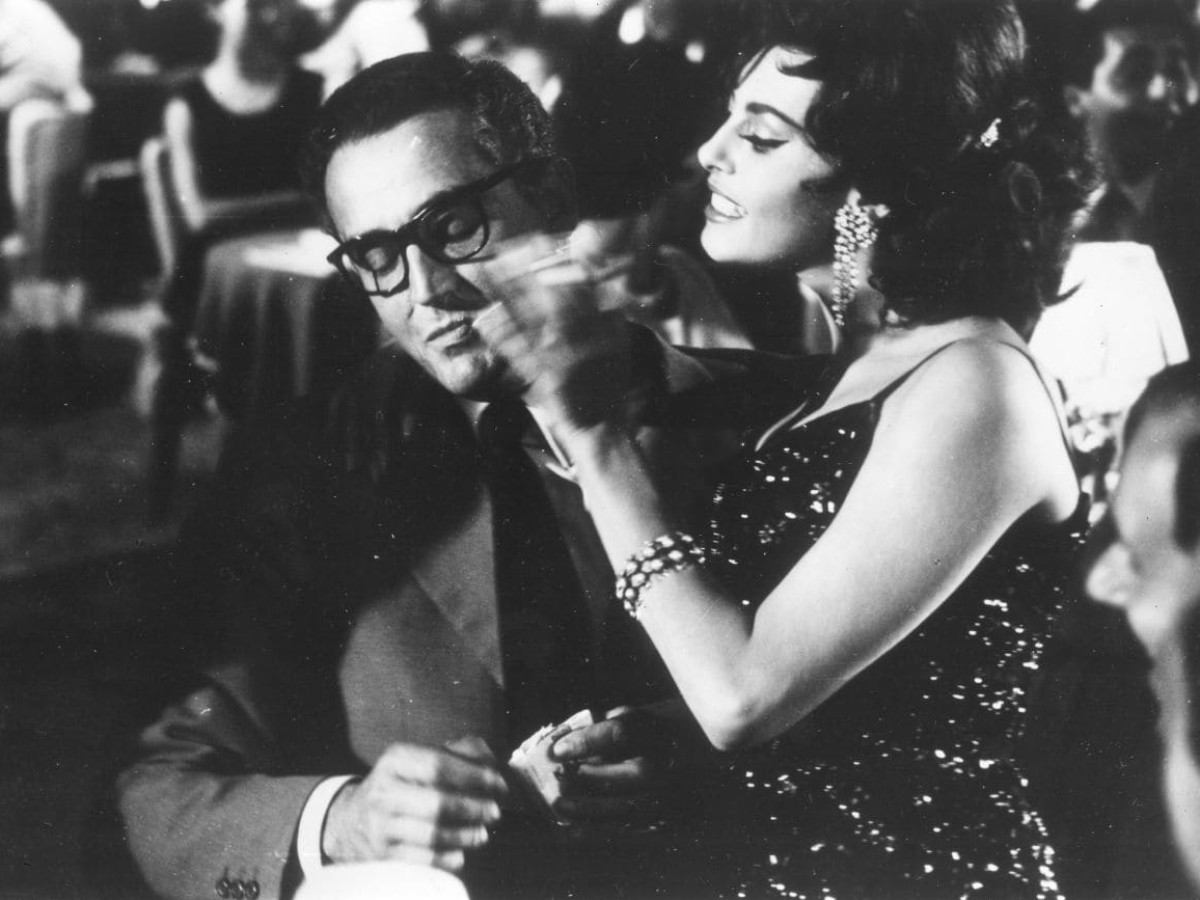

In Il vigile (The Traffic Policeman, 1962), Sordi plays a policeman for Zampa who is intoxicated by his new authority. Zampa compared this frantic comedic feat with his rousing drama Processo alla città (The City Stands Trial, 1952), which uses a historical case to address the machinations of the Neapolitan Camorra for the first time: Both films are ultimately about power. From 1940s Neorealism to its "rosy" variation of the 1950s, the sharp 1960s comedies and his films in the 1970s with their marks of grotesque darkness, Zampa spent decades keeping a close watch on the methods used to ensure oneself a piece of the pie: A panorama of decay covered in the widest array of tones, be it melodramatic as in his Moravia adaptation La romana (Woman of Rome, 1954) with Gina Lollobrigida or sarcastic as in the vendetta farce Una questione d'onore (A Question of Honor, 1966) starring Ugo Tognazzi.

It was with Tognazzi that Salce established himself in the early 1960s as an extraordinary film director with an unusual flair for social satire. Whereas Zampa received international acclaim during his lifetime, Salce remained one of Italy's best kept secrets. In his homeland, his misshapen jaw earned him the nickname the "man with the crooked mouth": After a bad car accident in his childhood, he was given a golden prosthetic which was pulled out when he was a POW in a German camp. His laconic journal entry: "1943–45: two difficult years."

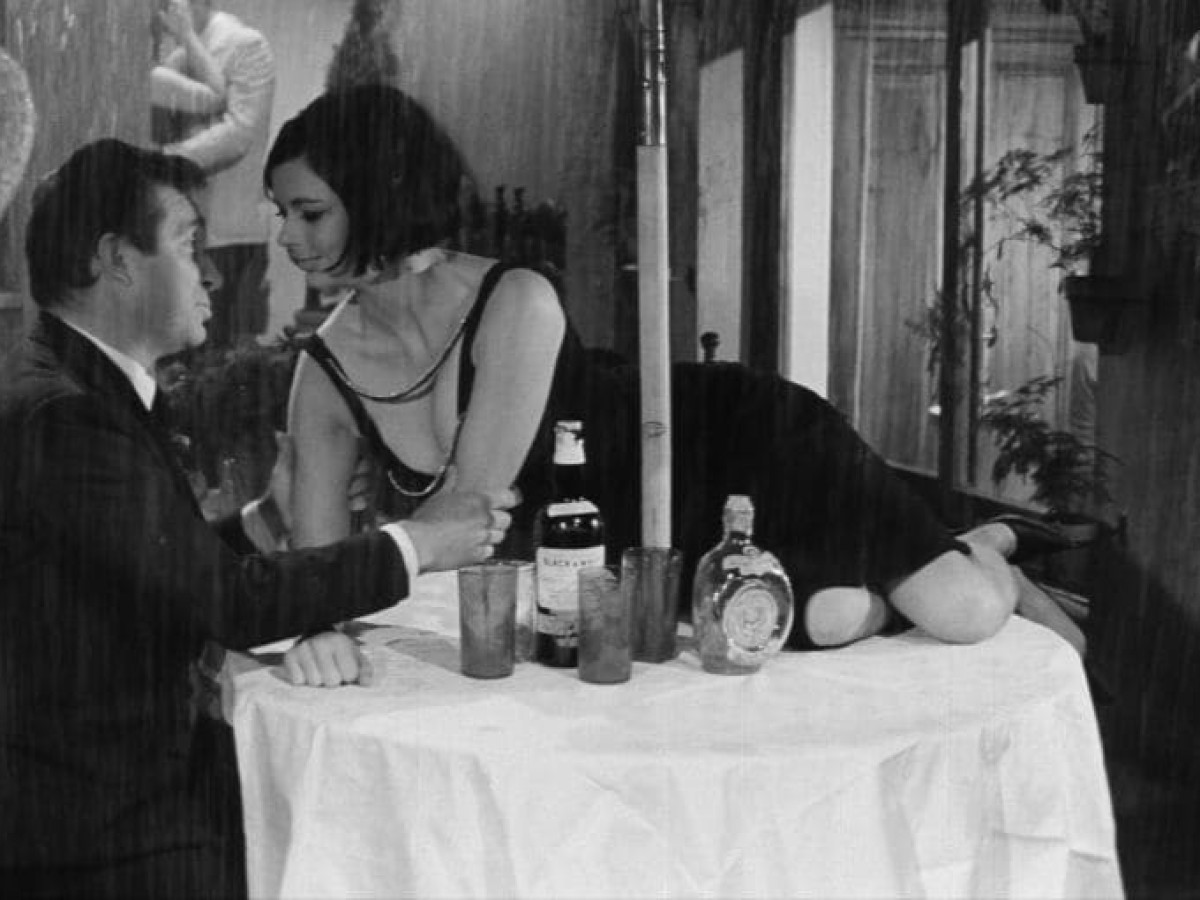

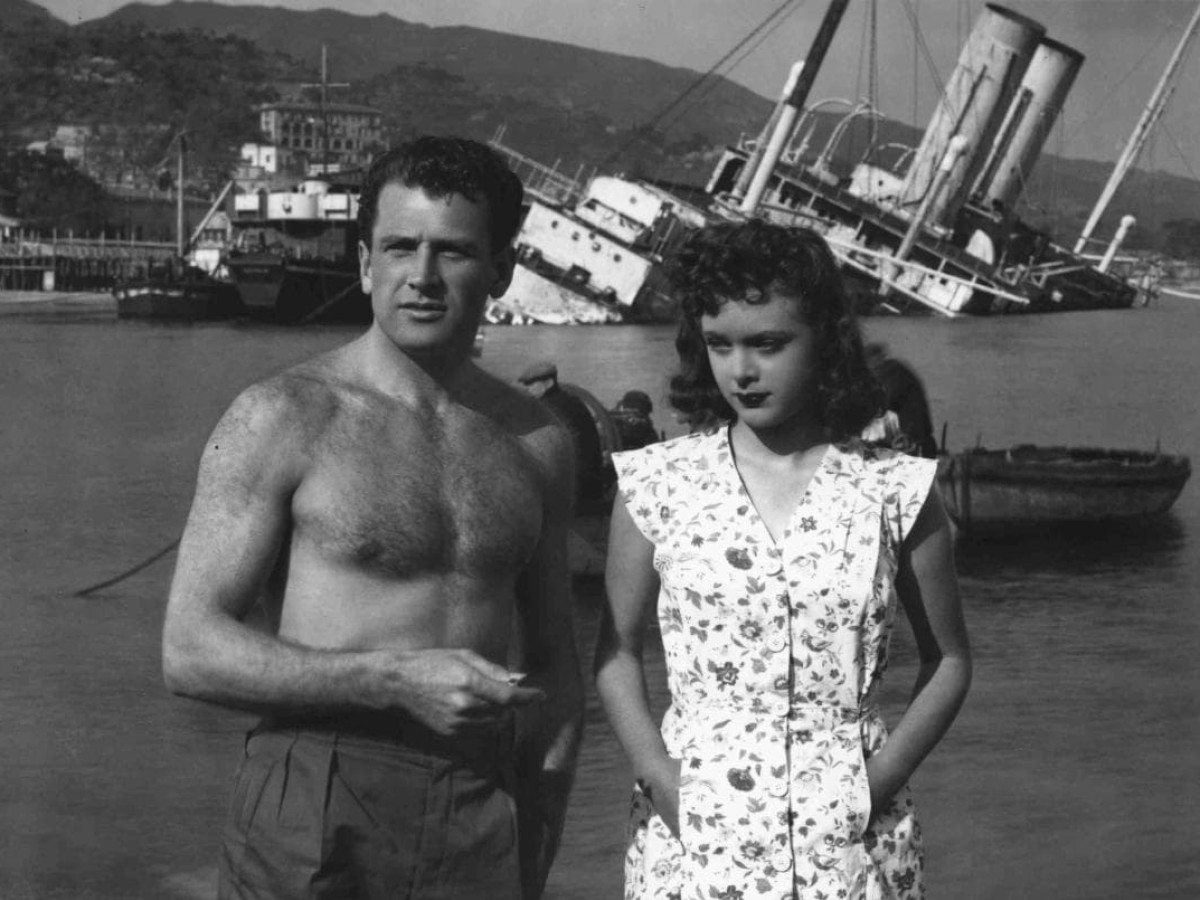

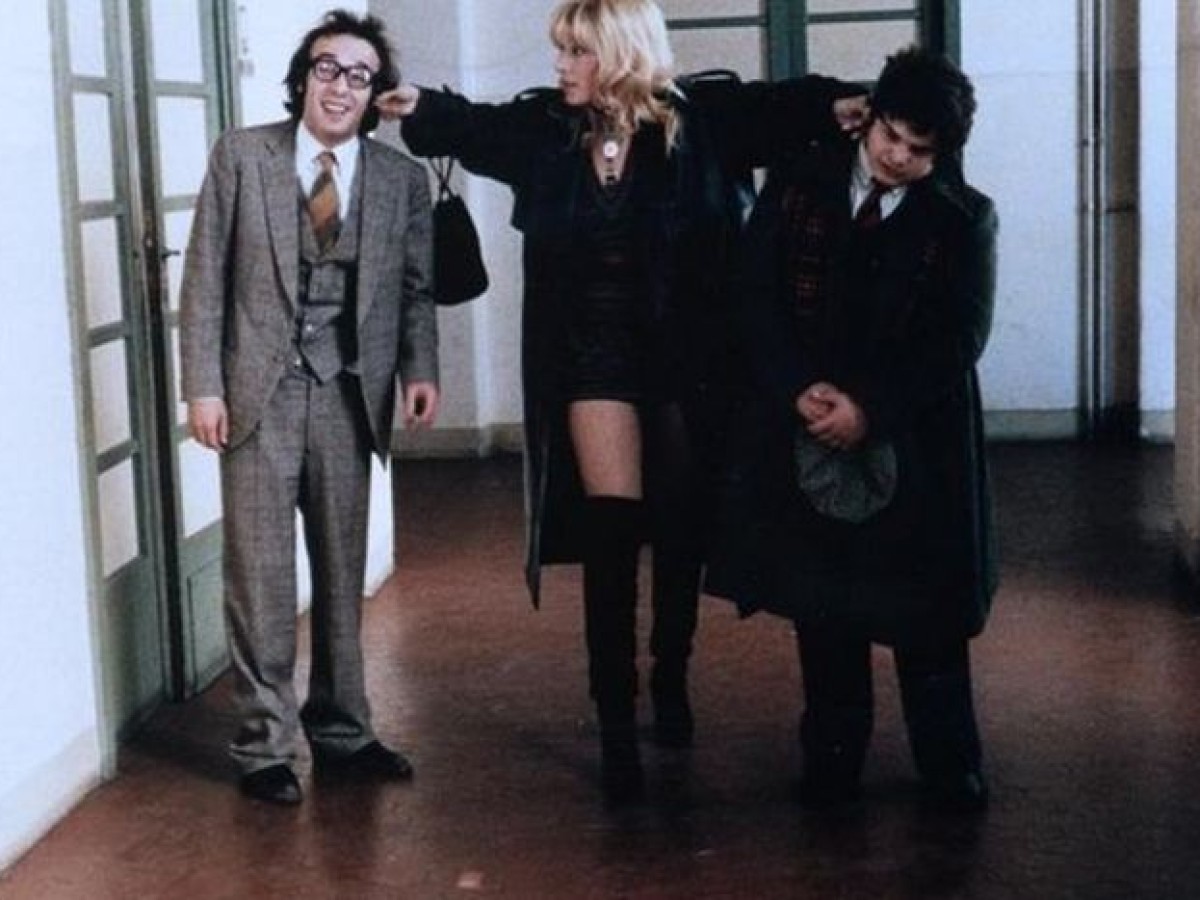

In the 1940s, he had already made a name for himself in theater, working with greats like Luchino Visconti and Vittorio Gassmann. He debuted as a movie actor (for Zampa) in 1946; in the 1950s, a stage tour brought him to Brazil, where he made his first films. Back in Italy, he found success with a brilliant trilogy of comedies which showed off Tognazzi's talent: Il federale (The Fascist, 1961), about the end of the fascist era, was followed by satirical genre pictures set in the present with melancholic undertones. In La voglia matta (Crazy Desire, 1962), Tognazzi falls in love with a teenage girl (Catherine Spaak) and searches in vain for a connection to youth culture; Le ore dell'amore (The Hours of Love, 1963) is a shattering report on the institution of marriage, which transforms Tognazzi's happy relationship (with Emmanuelle Riva) into a torturous forced pairing.

Like Zampa, Salce intensified his approach to the commedia all'italiana, defining it as the "discovery of urban reality and the possibility of using this reality as a source for ideas." In his films too, the tragicomic nuances give way to grotesquery and reflect social changes: A crisis in his personal life (his second wife left him at the end of the 1960s for his best friend Gassmann) intensified this development. In the end, Salce managed to unleash a comic energy which led him to new flights of absurdity: Works like Basta guardarla (1970) and the Fantozzi films, once dismissed by critics, are now cult classics.

The critical disdain for popular comedy may have partly been overcome, but the situation of film prints is becoming harder across the board. To top it off, prints that were still accessible a few years ago are no longer in circulation. Even if for a while now, we have taken this into consideration when conceiving our series, it is no longer possible to hold this kind of retrospective with almost exclusively 35mm prints. We would have liked to show more films by Salce (and Zampa), but many are now only digitally available for theatrical screenings, and just as many are no longer available at all. (Christoph Huber / Translation: Ted Fendt)

Luciano Salce's son Emanuele Salce will be our guest for the opening and introduce films by his father.

In collaboration with Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Vienna

Combining razor-sharp satire and popular entertainment, the commedia all'italiana was world renowned between the 1950s and the 1980s. In 2010, we dedicated a major retrospective to this national genre and have subsequently explored its many varieties in other contexts, but there still remains much to discover in the wide field of Italian comedy. To start off the year, we turn to two underappreciated directors who perfectly concentrate the commedia's essence of satire and social critique: In the pointed, contemporary filmic documents of Romans Luigi Zampa (1905–1991) and Luciano Salce (1922–1989), we find a comprehensive and unsparing portrait of social and moral progress.

There is a direct lineage between Zampa's classic moral comedy Anni difficili (Difficult Years, 1948) and its grappling with the fascist era, and the side-splitting anthology about the frustrated existence of middle class salaried workers in Salce's brilliant one-two punch Fantozzi (1975) and Il secondo tragico Fantozzi (1976) with Paolo Villaggio in the title role. Power and obedience, corruption and the urge for social recognition, and corruptibility and blind infatuation are recurring themes. L'arte di arrangiarsi (The Art of Getting Along, 1955) is the not-so-ambiguous title of one of Zampa's major works, in which a small municipal clerk (master mime Alberto Sordi) smoothly and spinelessly slips from one political regime to the next between 1913 and 1953: socialist, fascist, communist, Christian democrat – the perfect opportunist.

In Il vigile (The Traffic Policeman, 1962), Sordi plays a policeman for Zampa who is intoxicated by his new authority. Zampa compared this frantic comedic feat with his rousing drama Processo alla città (The City Stands Trial, 1952), which uses a historical case to address the machinations of the Neapolitan Camorra for the first time: Both films are ultimately about power. From 1940s Neorealism to its "rosy" variation of the 1950s, the sharp 1960s comedies and his films in the 1970s with their marks of grotesque darkness, Zampa spent decades keeping a close watch on the methods used to ensure oneself a piece of the pie: A panorama of decay covered in the widest array of tones, be it melodramatic as in his Moravia adaptation La romana (Woman of Rome, 1954) with Gina Lollobrigida or sarcastic as in the vendetta farce Una questione d'onore (A Question of Honor, 1966) starring Ugo Tognazzi.

It was with Tognazzi that Salce established himself in the early 1960s as an extraordinary film director with an unusual flair for social satire. Whereas Zampa received international acclaim during his lifetime, Salce remained one of Italy's best kept secrets. In his homeland, his misshapen jaw earned him the nickname the "man with the crooked mouth": After a bad car accident in his childhood, he was given a golden prosthetic which was pulled out when he was a POW in a German camp. His laconic journal entry: "1943–45: two difficult years."

In the 1940s, he had already made a name for himself in theater, working with greats like Luchino Visconti and Vittorio Gassmann. He debuted as a movie actor (for Zampa) in 1946; in the 1950s, a stage tour brought him to Brazil, where he made his first films. Back in Italy, he found success with a brilliant trilogy of comedies which showed off Tognazzi's talent: Il federale (The Fascist, 1961), about the end of the fascist era, was followed by satirical genre pictures set in the present with melancholic undertones. In La voglia matta (Crazy Desire, 1962), Tognazzi falls in love with a teenage girl (Catherine Spaak) and searches in vain for a connection to youth culture; Le ore dell'amore (The Hours of Love, 1963) is a shattering report on the institution of marriage, which transforms Tognazzi's happy relationship (with Emmanuelle Riva) into a torturous forced pairing.

Like Zampa, Salce intensified his approach to the commedia all'italiana, defining it as the "discovery of urban reality and the possibility of using this reality as a source for ideas." In his films too, the tragicomic nuances give way to grotesquery and reflect social changes: A crisis in his personal life (his second wife left him at the end of the 1960s for his best friend Gassmann) intensified this development. In the end, Salce managed to unleash a comic energy which led him to new flights of absurdity: Works like Basta guardarla (1970) and the Fantozzi films, once dismissed by critics, are now cult classics.

The critical disdain for popular comedy may have partly been overcome, but the situation of film prints is becoming harder across the board. To top it off, prints that were still accessible a few years ago are no longer in circulation. Even if for a while now, we have taken this into consideration when conceiving our series, it is no longer possible to hold this kind of retrospective with almost exclusively 35mm prints. We would have liked to show more films by Salce (and Zampa), but many are now only digitally available for theatrical screenings, and just as many are no longer available at all. (Christoph Huber / Translation: Ted Fendt)

Luciano Salce's son Emanuele Salce will be our guest for the opening and introduce films by his father.

In collaboration with Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Vienna

Related materials

Link Contributors

For each series, films are listed in screening order.